* About W3C and the Web

* Why accessibility is important

* Why internationalization is important

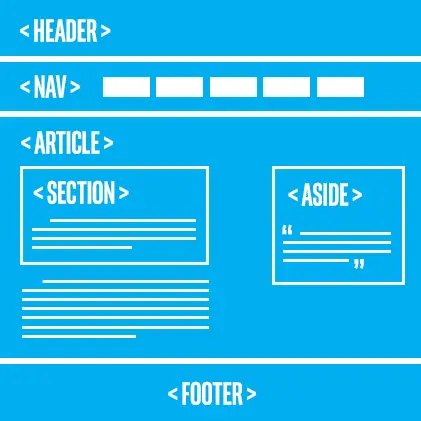

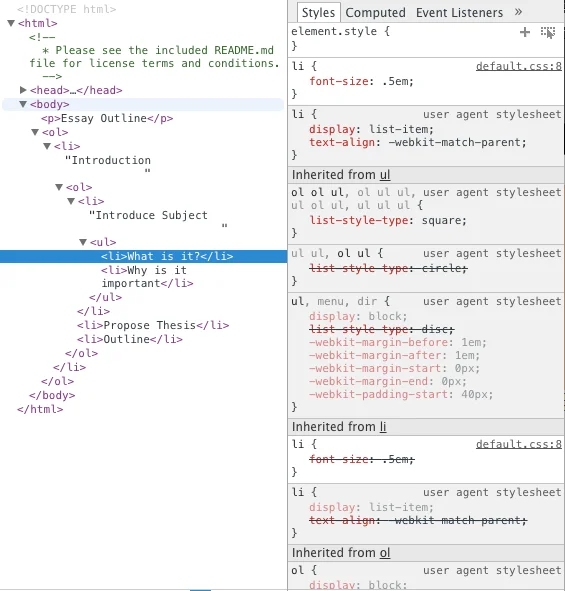

1.1 Introduction to Module 1 - my first web page

1.2 The big three; HTTP, HTML and URL

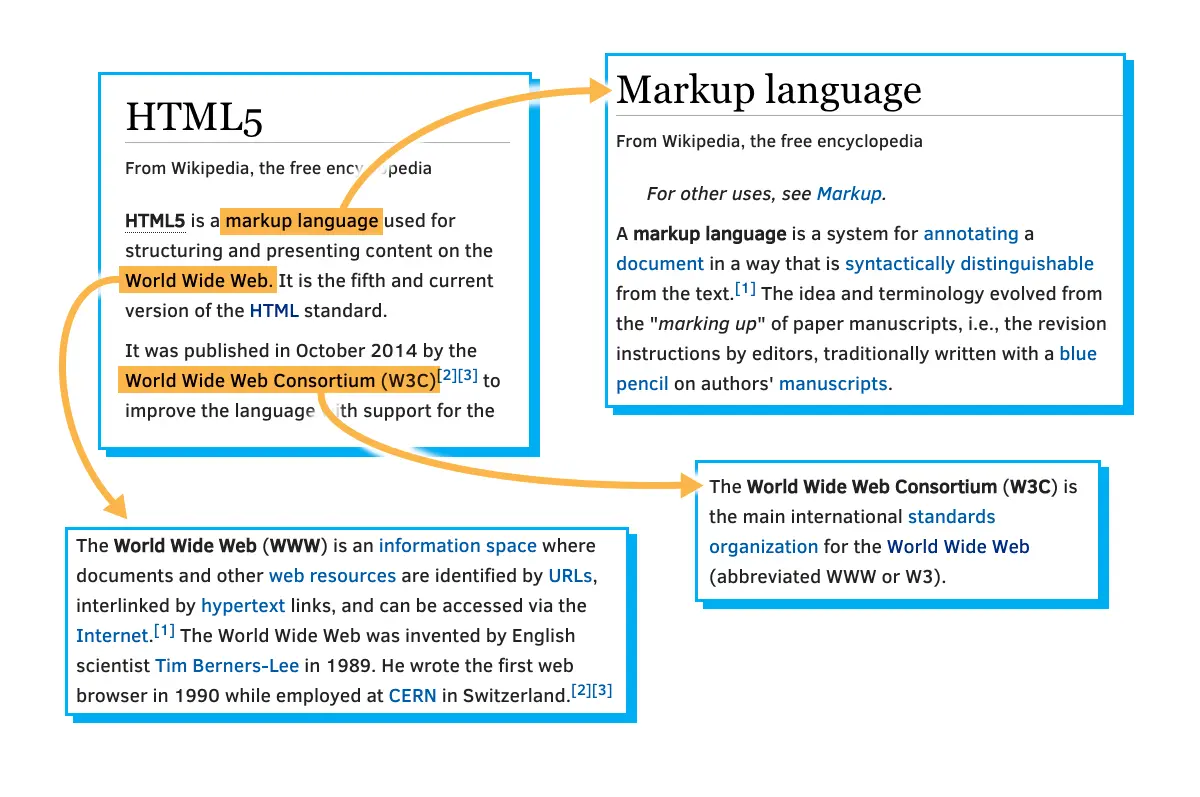

1.3 Putting the "M" in HTML

1.4 Character encoding

1.5 Best practices - Learning from mistakes of others

1.6 Tags we have used & more

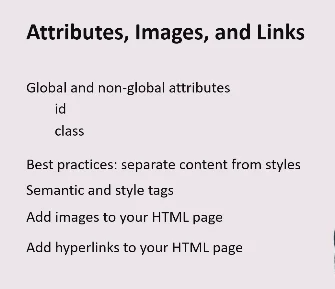

2.1 Introduction to Module 2 - attributes, images & links

2.2 Attributes

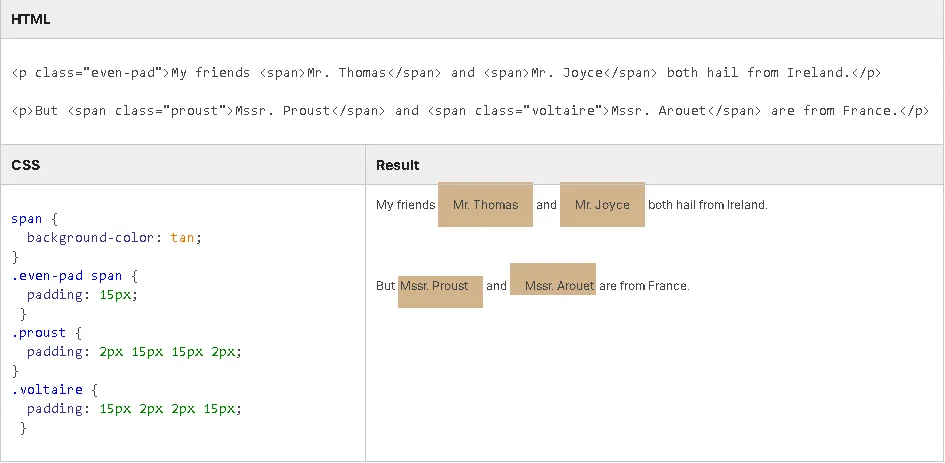

2.3 Semantic Meaning - separating content & style

2.4 Images

2.5 Hyperlinks

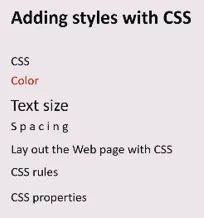

3.1 Introduction to Module 3 - adding style with css

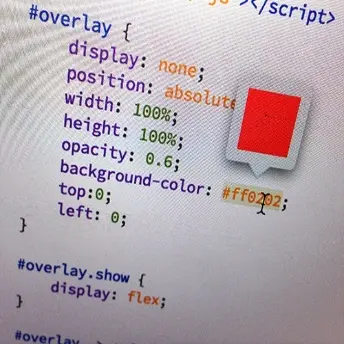

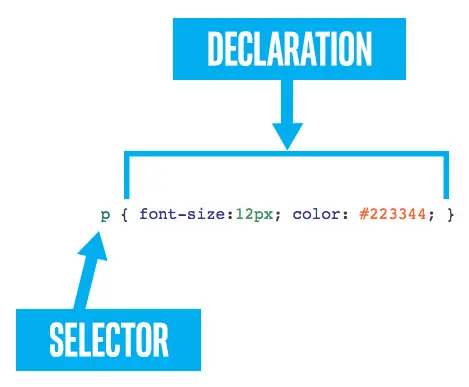

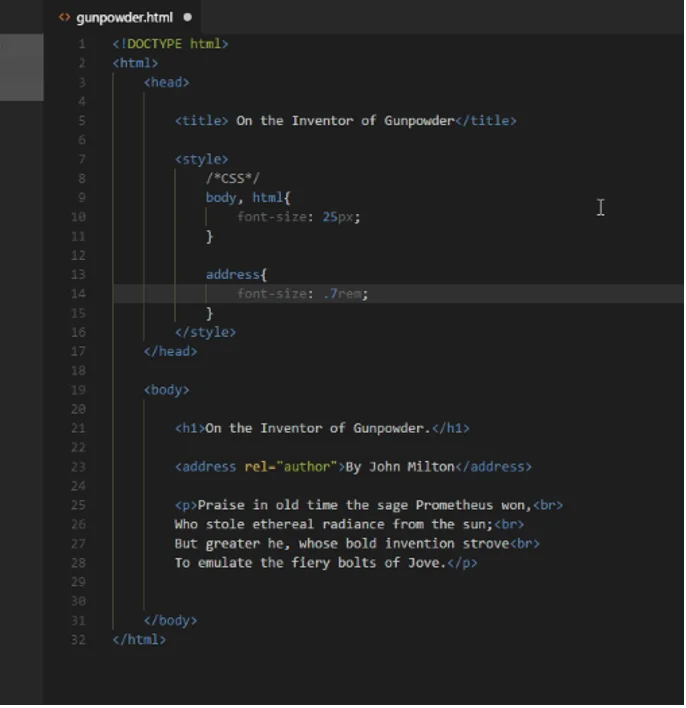

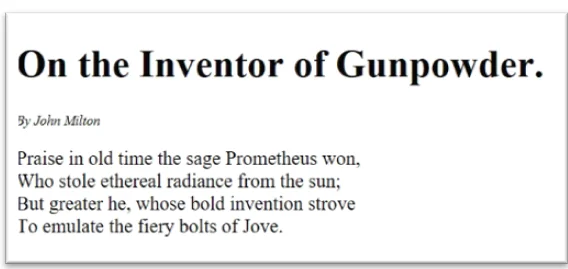

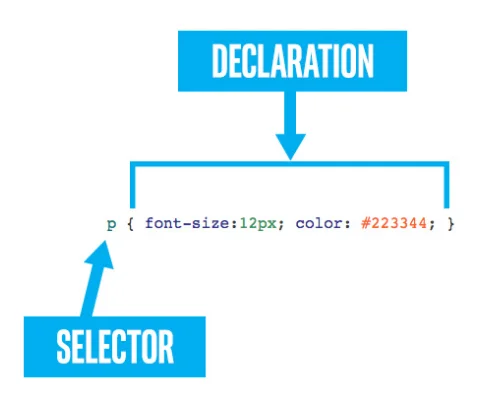

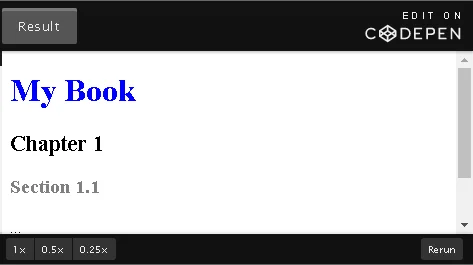

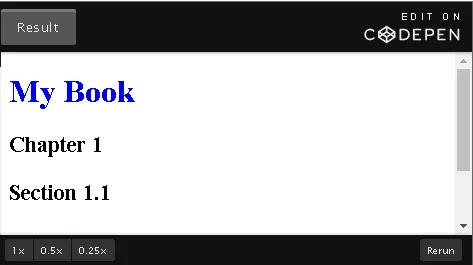

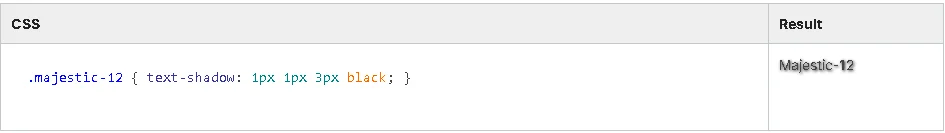

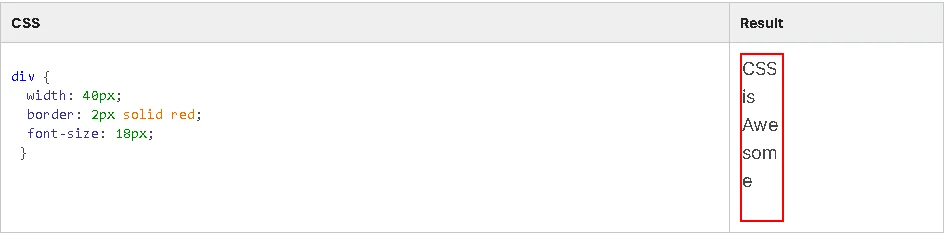

3.2 Style & Link tags - CSS basic syntax

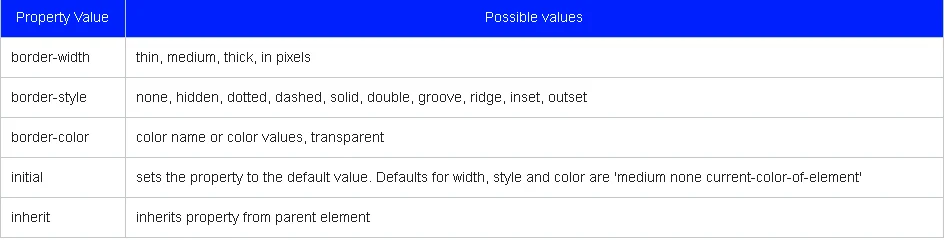

3.3 CSS properties

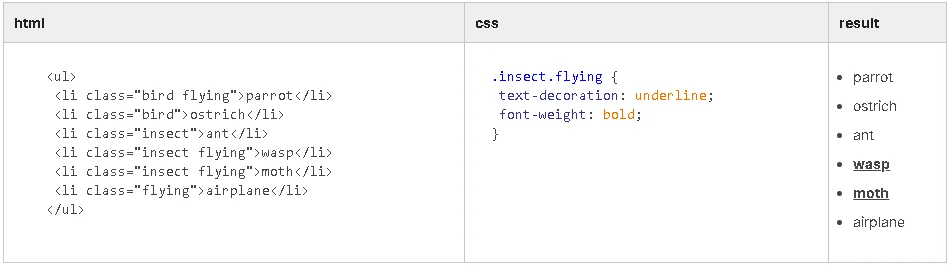

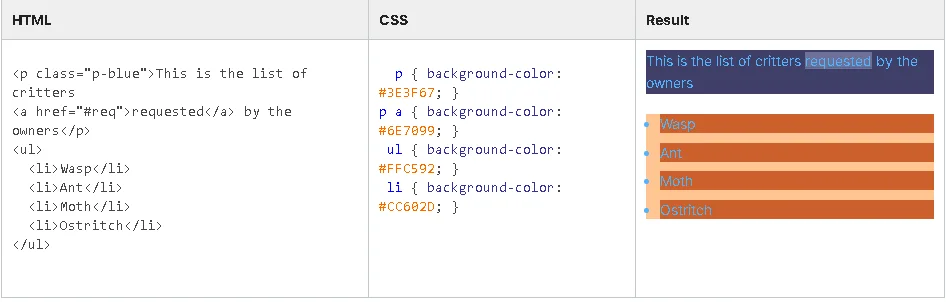

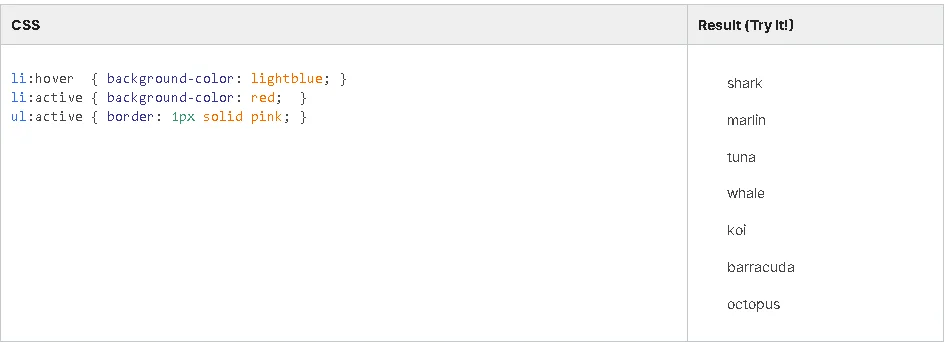

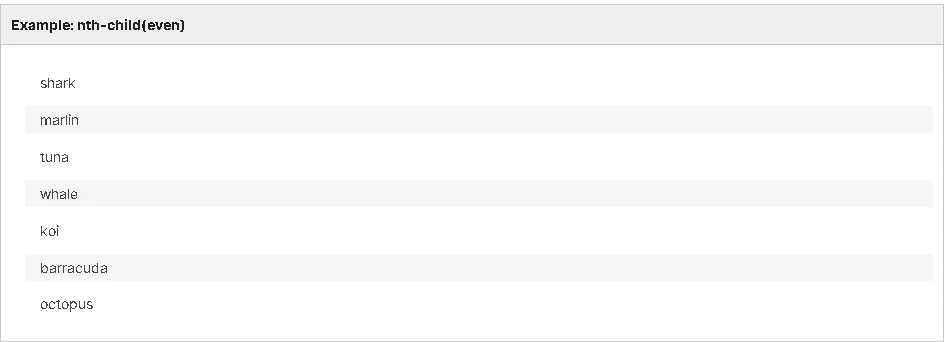

3.4 Styling Lists and Selectors

4.1 Introduction to Module 4 - fixing & debugging

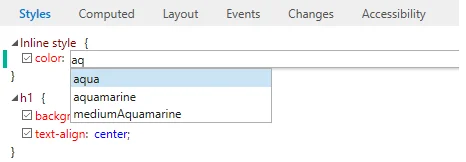

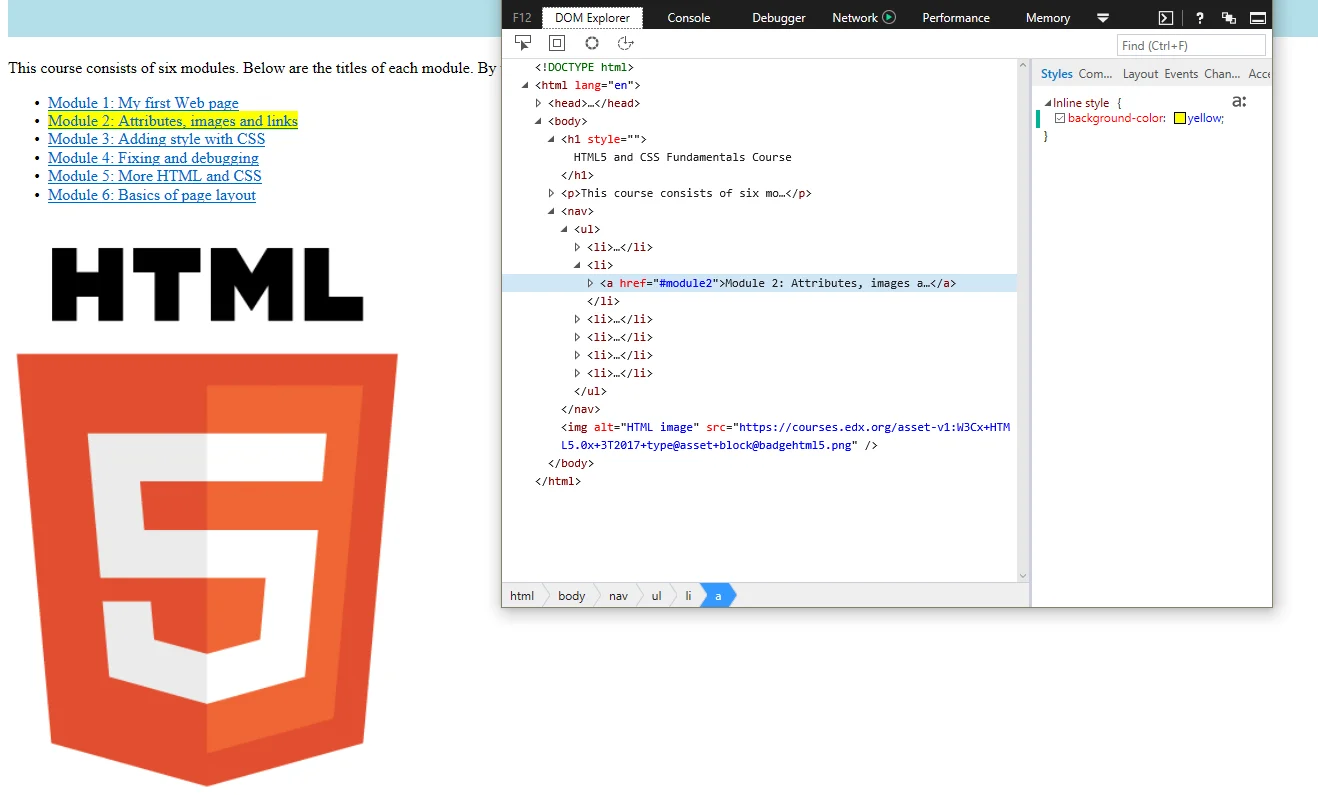

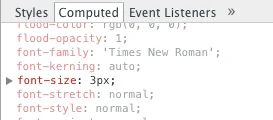

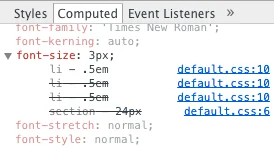

4.2 Debugging Tools and HTML5

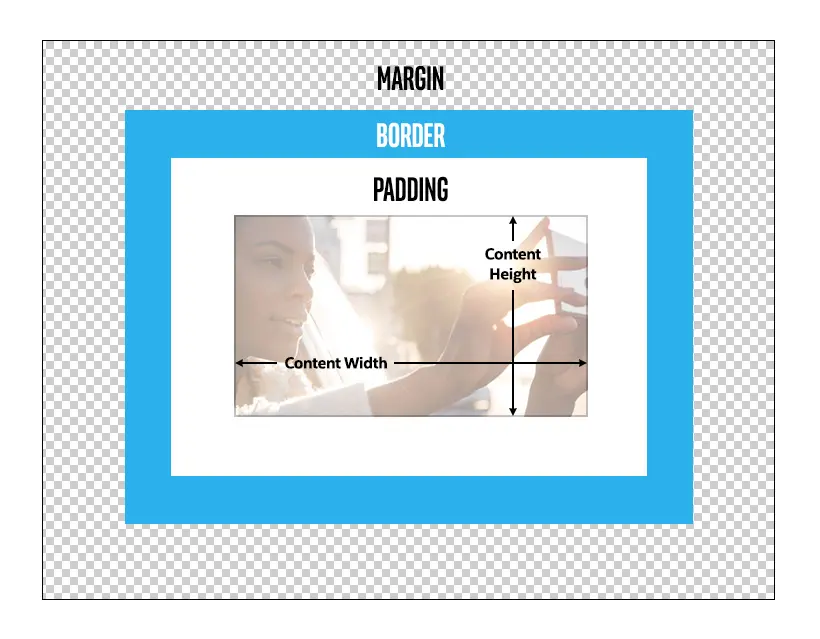

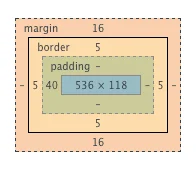

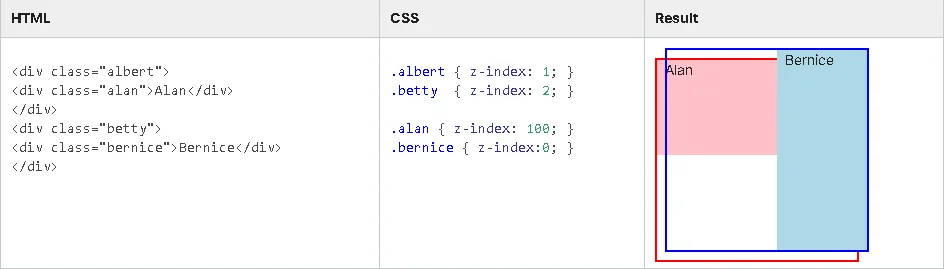

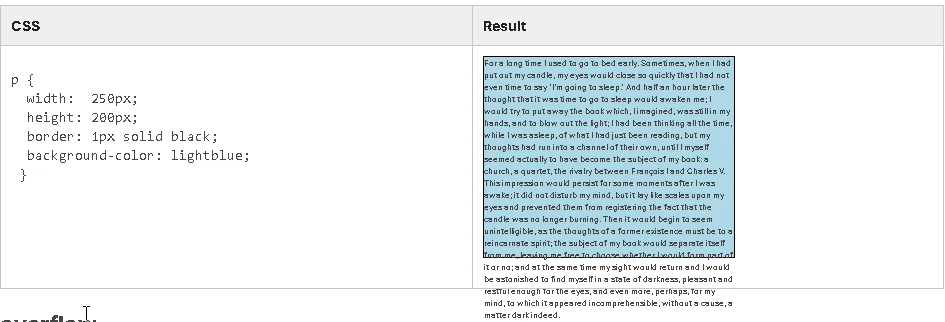

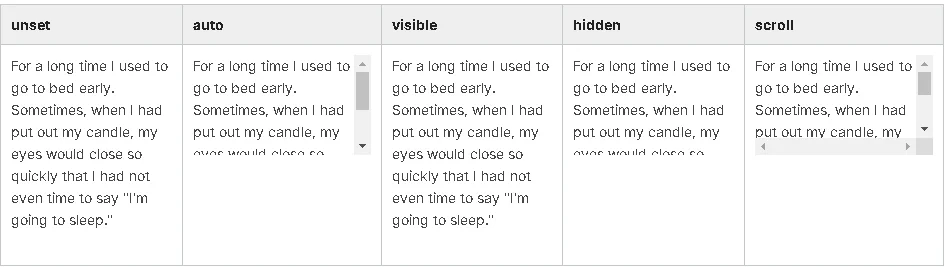

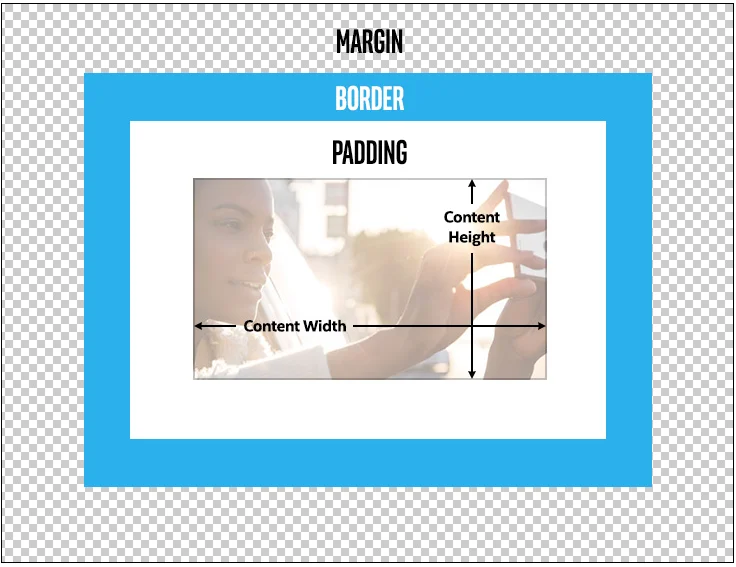

4.3 Debugging and the CSS Box Model

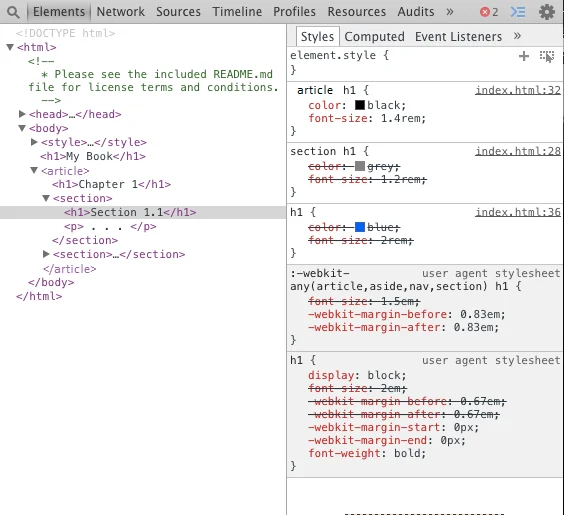

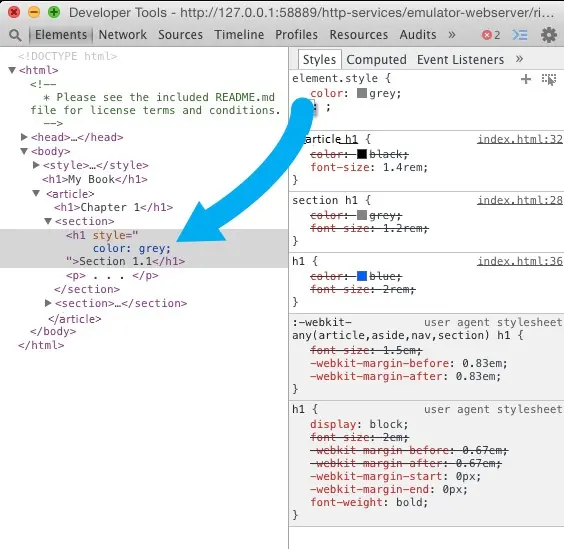

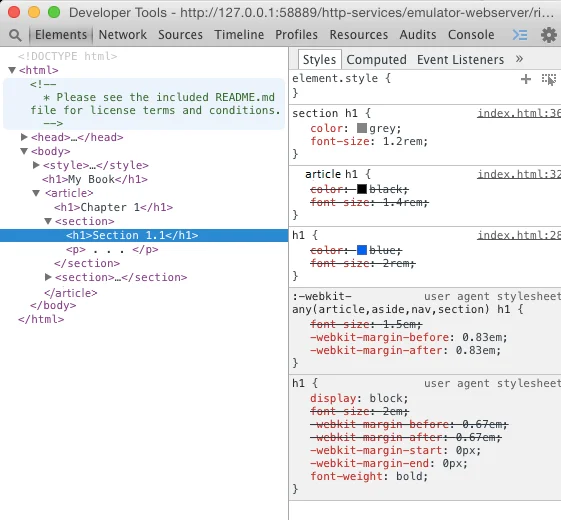

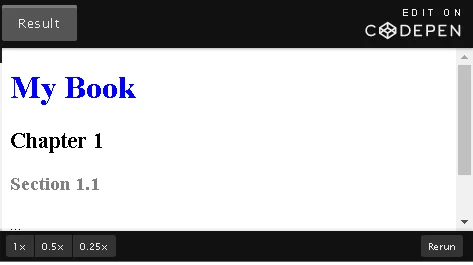

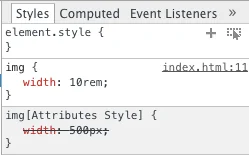

4.4 Debugging CSS Precedence

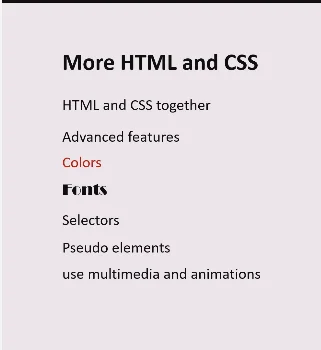

5.1 Introduction to Module 5 - more html5 and css3

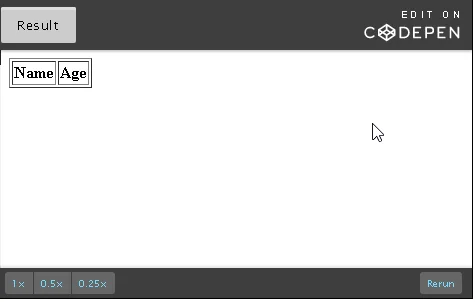

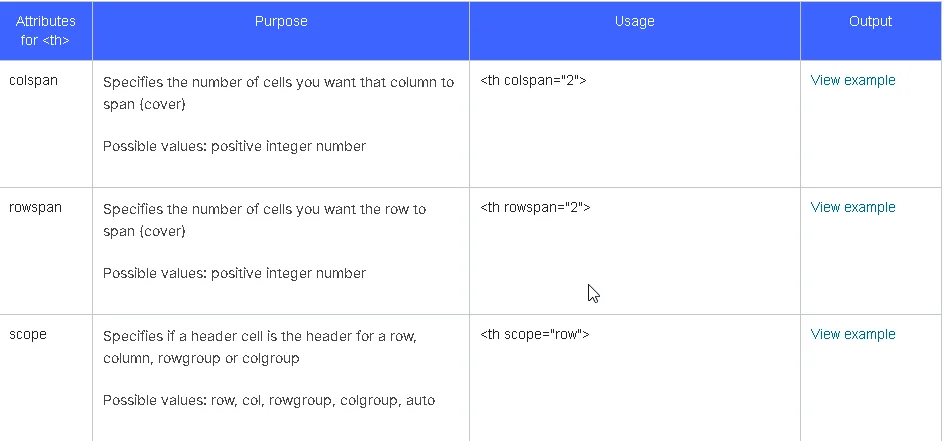

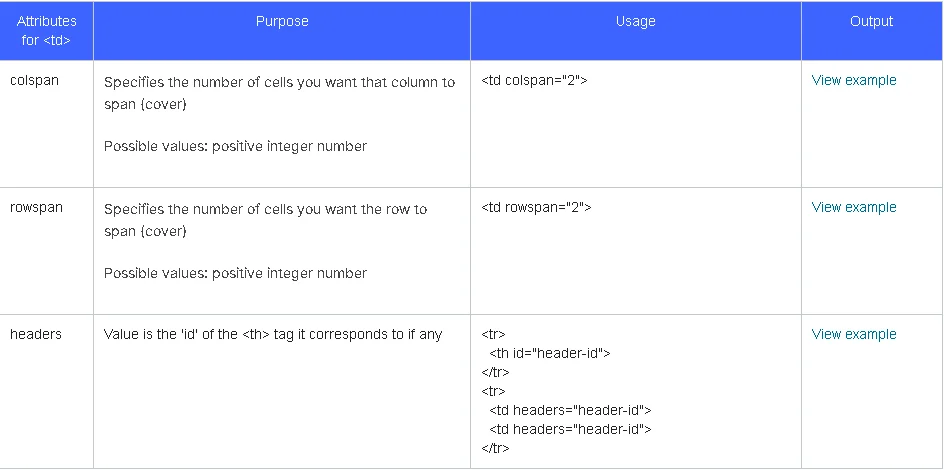

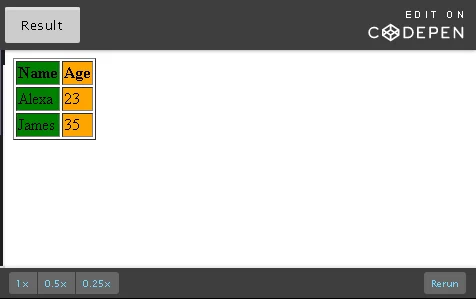

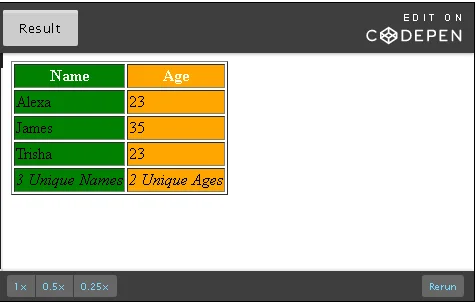

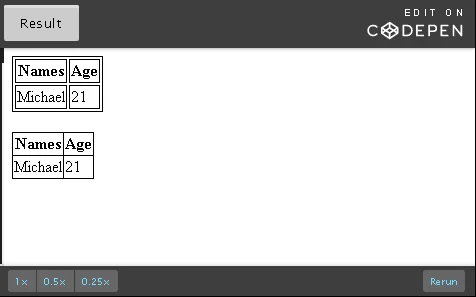

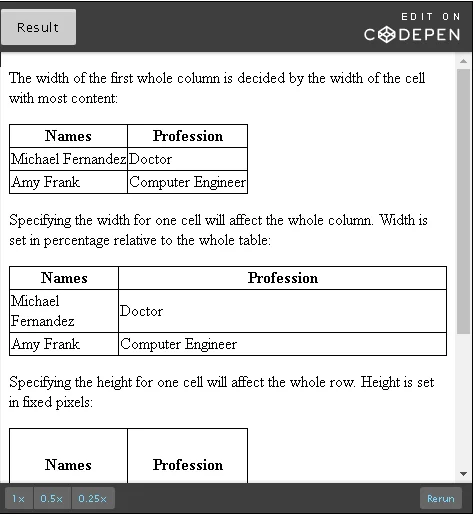

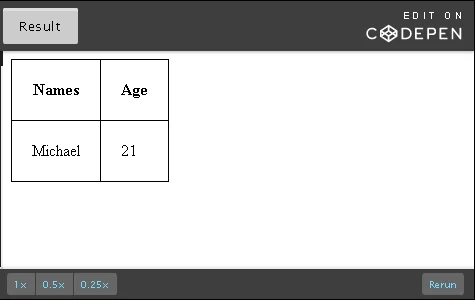

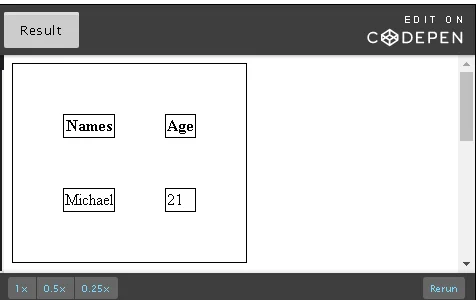

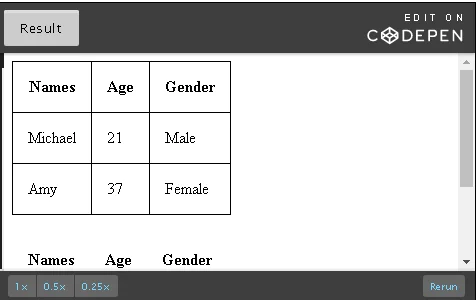

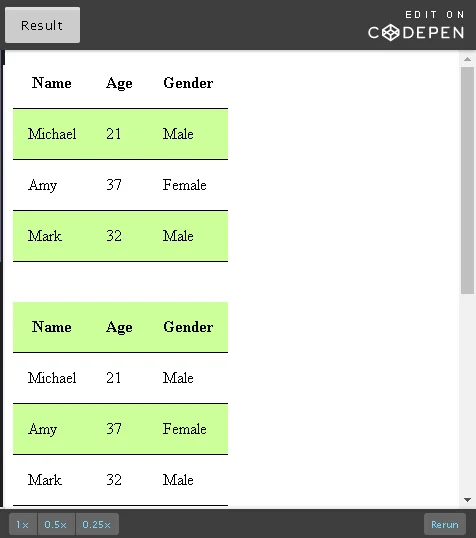

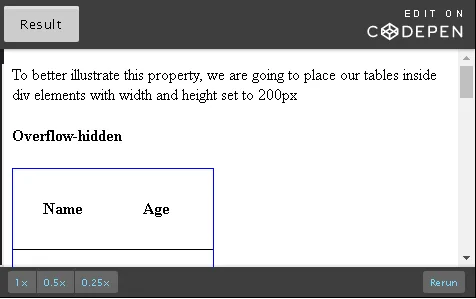

5.2 Tables

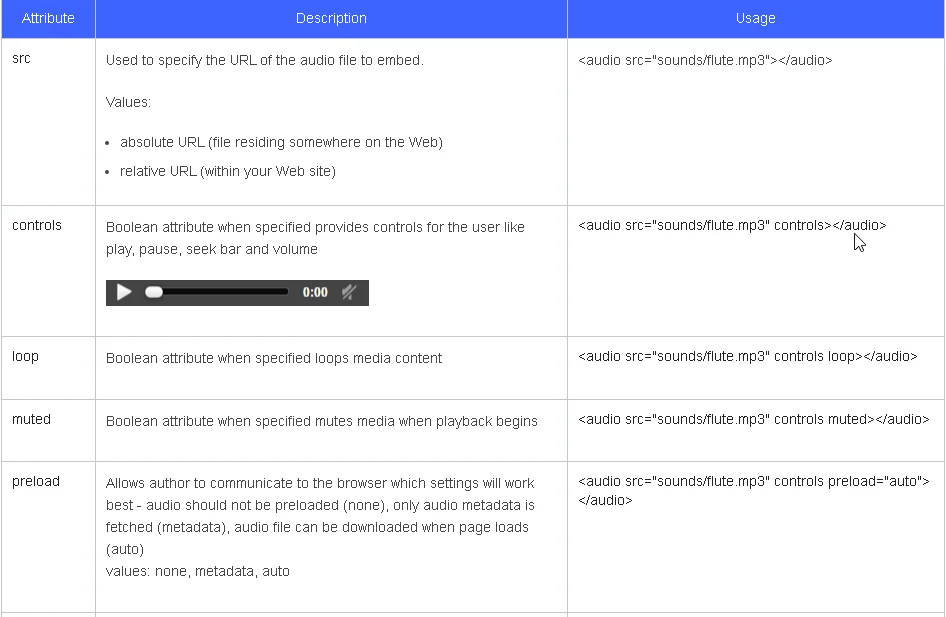

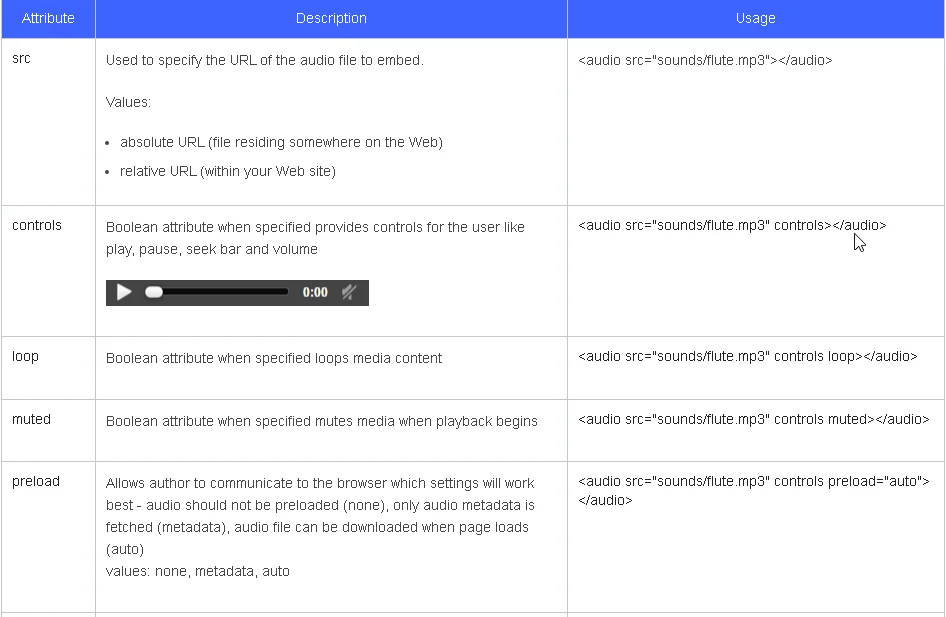

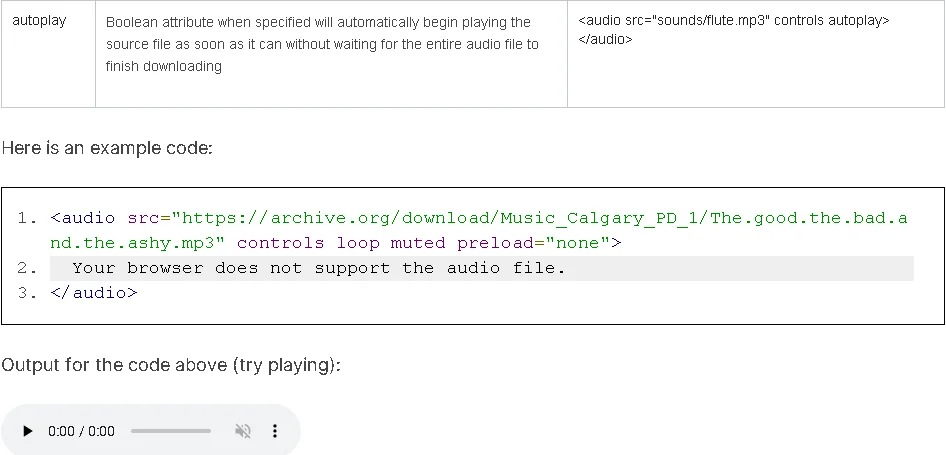

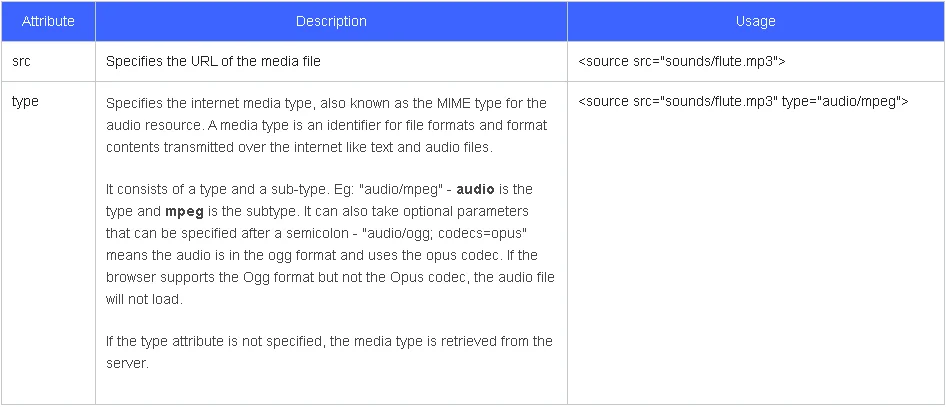

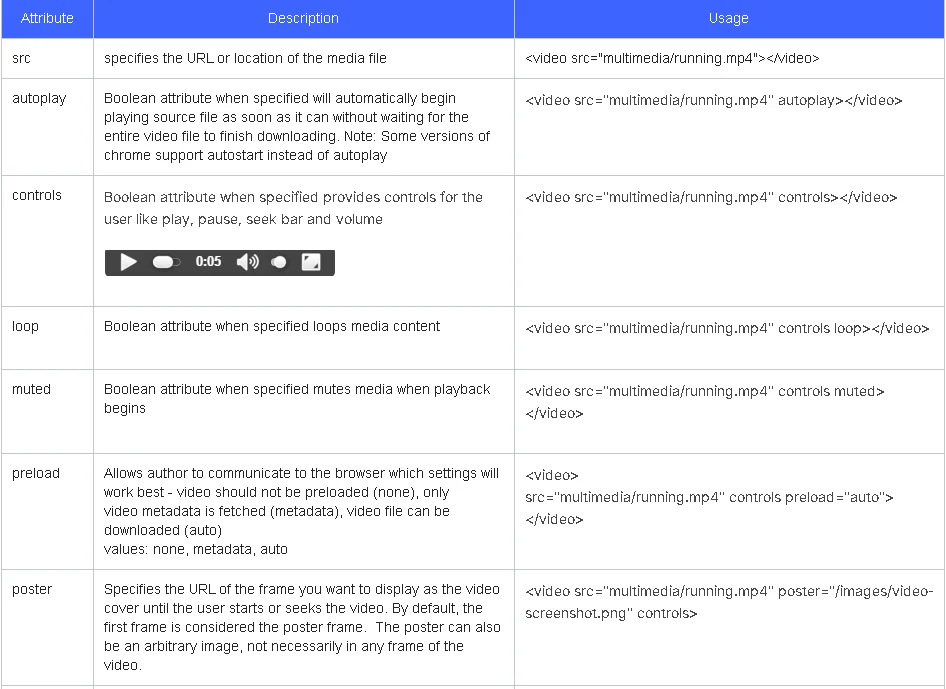

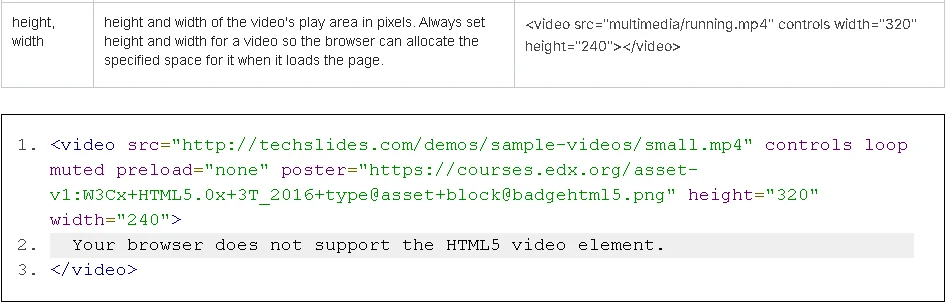

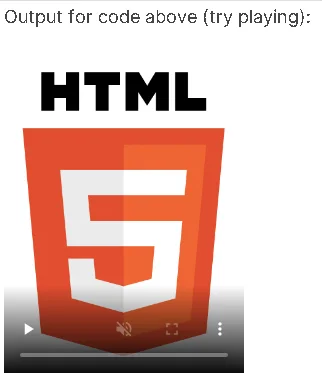

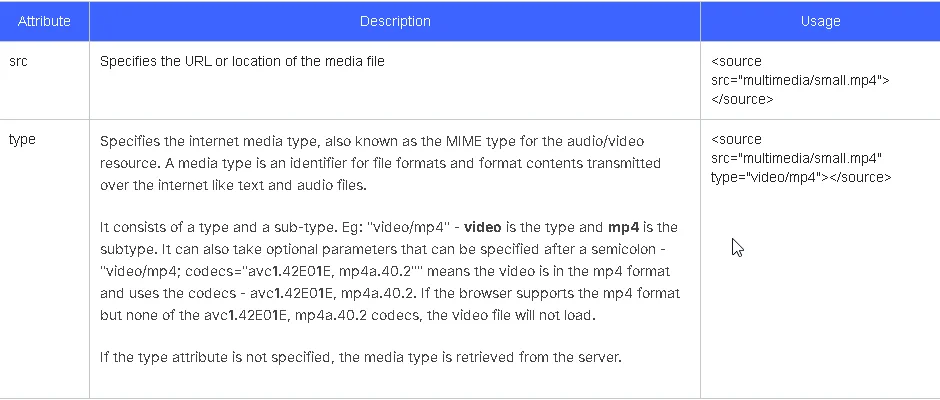

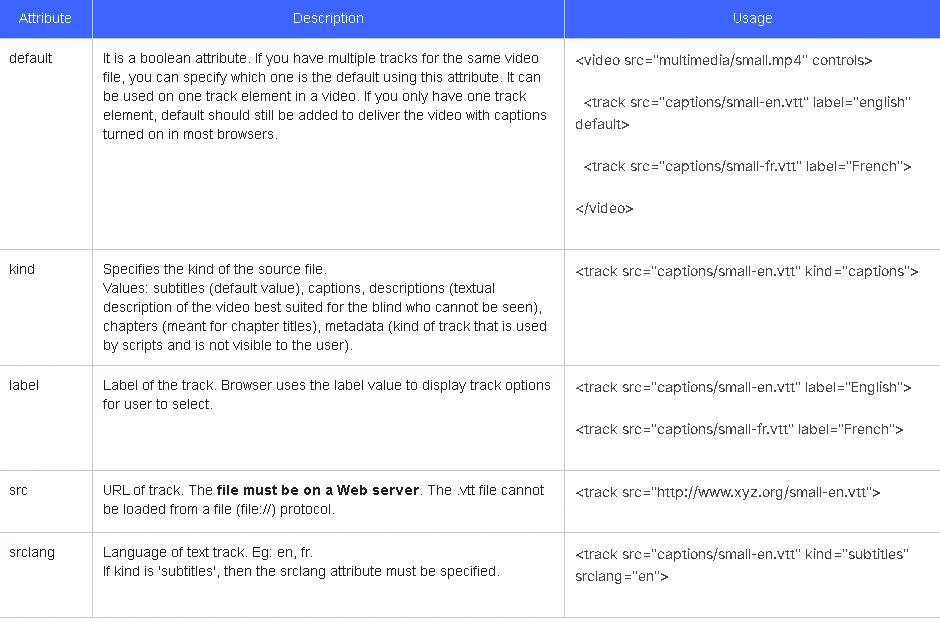

5.3 Multimedia - the audio element

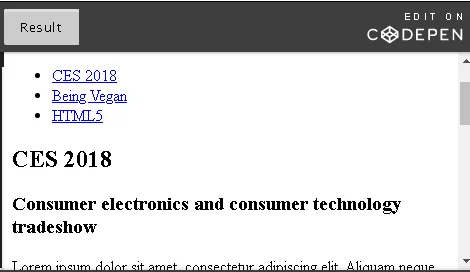

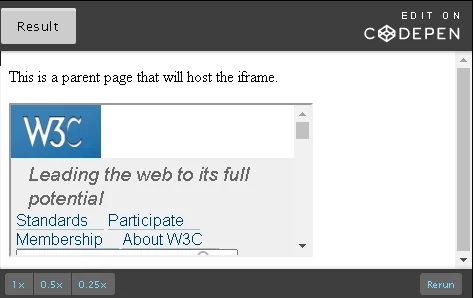

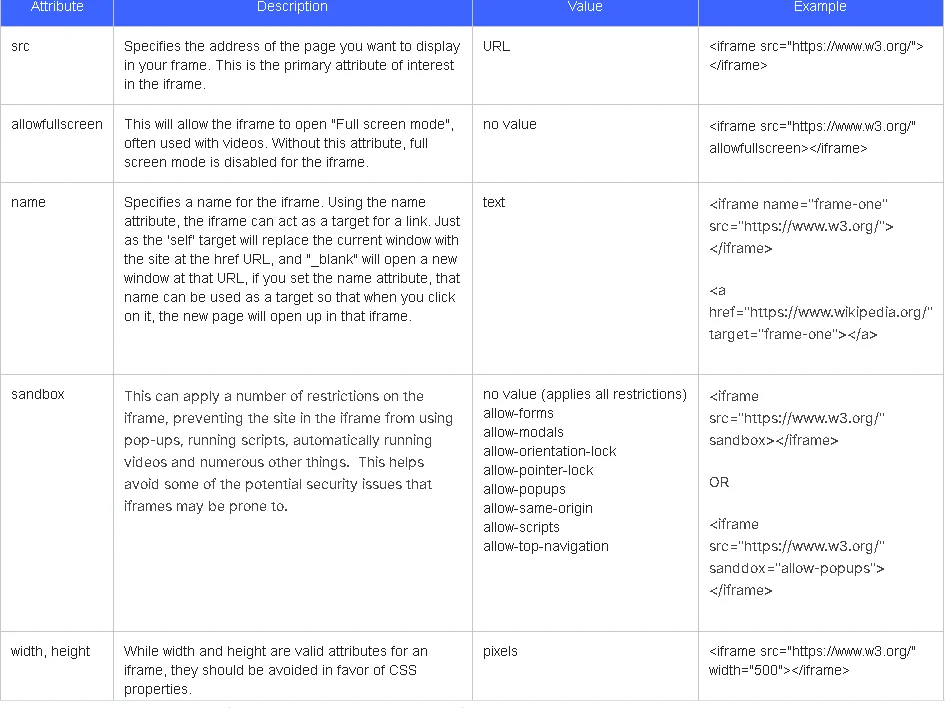

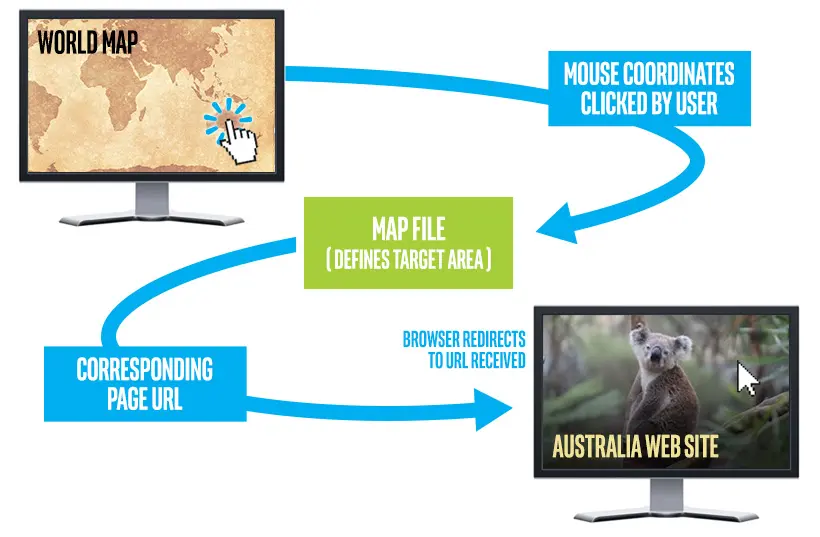

5.4 Embedding Content - the iframes tag

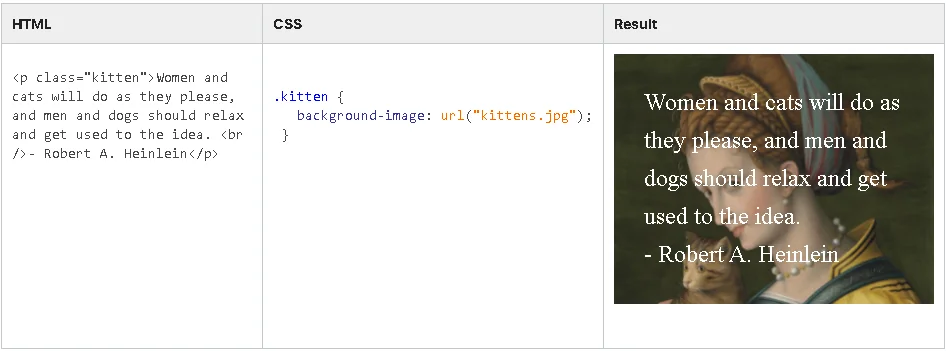

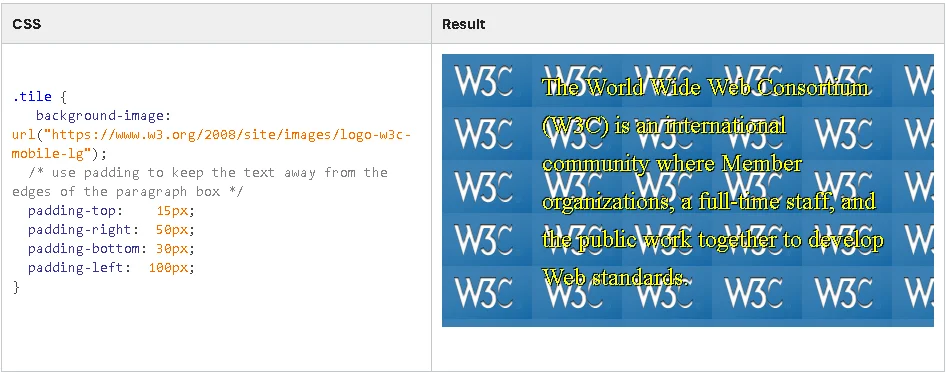

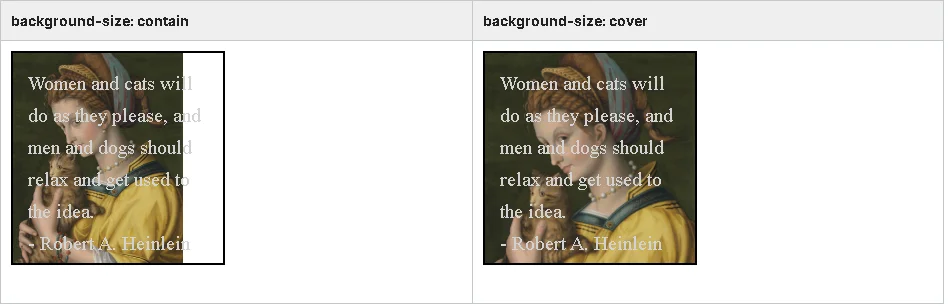

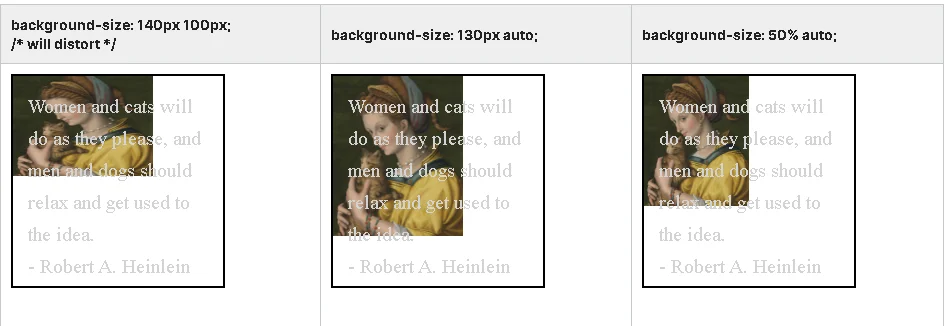

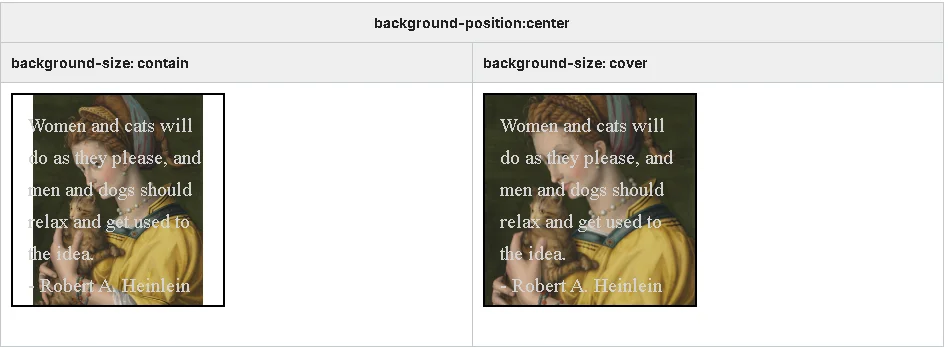

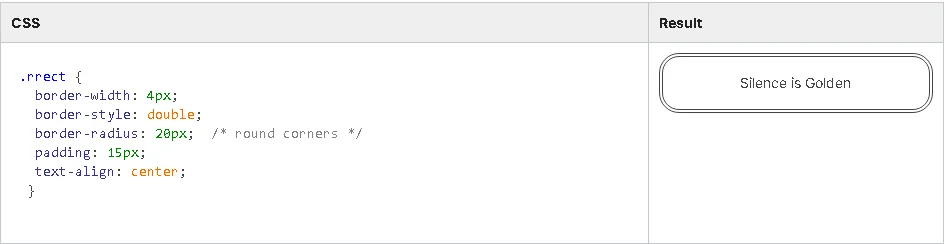

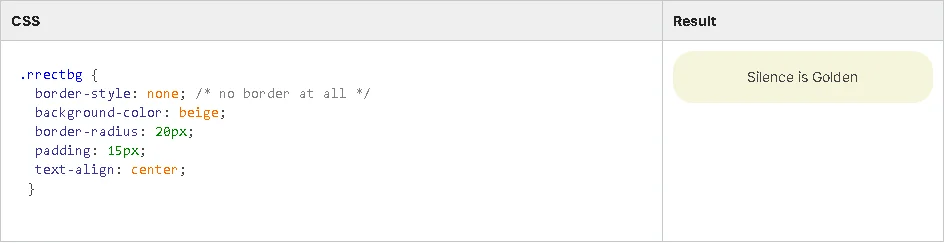

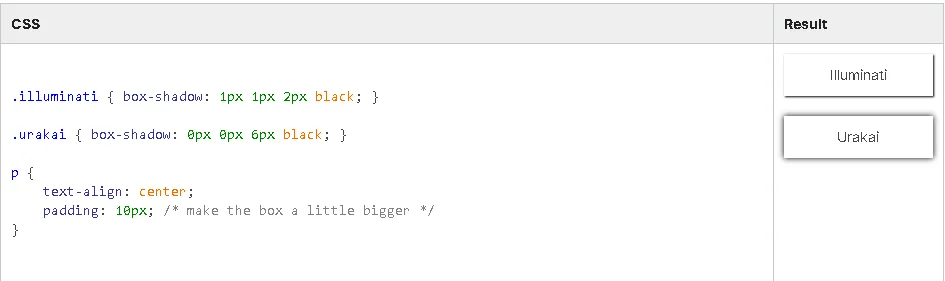

5.5 CSS Tricks - decorative images & backgrounds

6.1 Introduction to Module 6 - basics of page layout

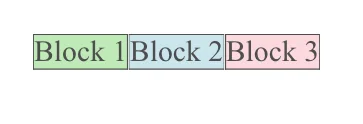

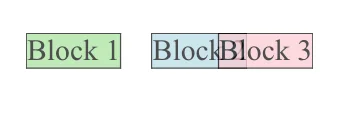

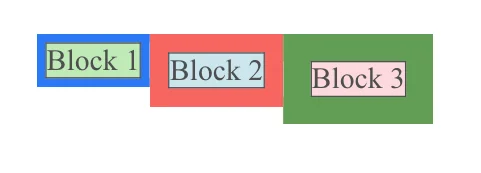

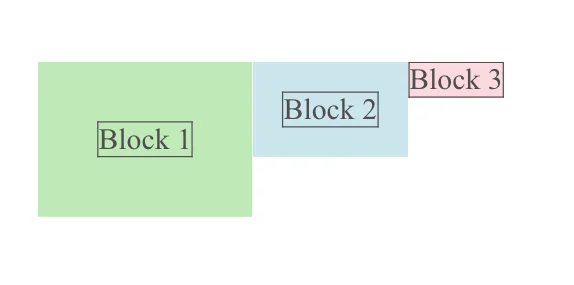

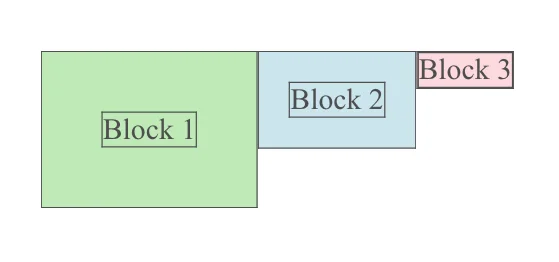

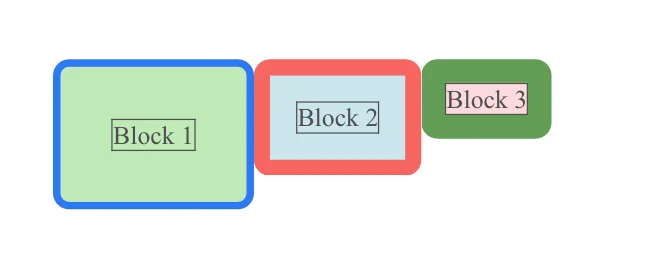

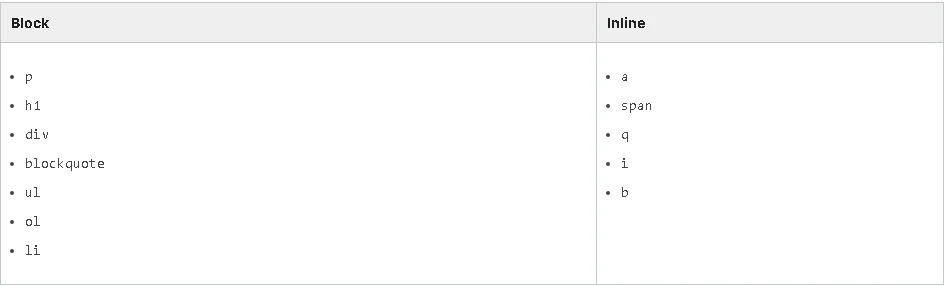

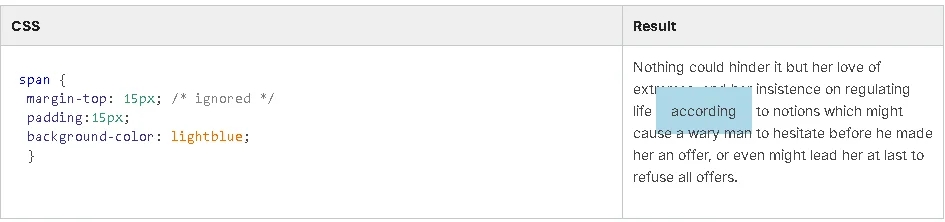

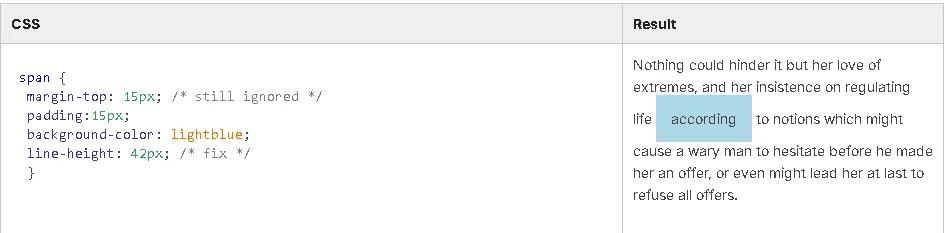

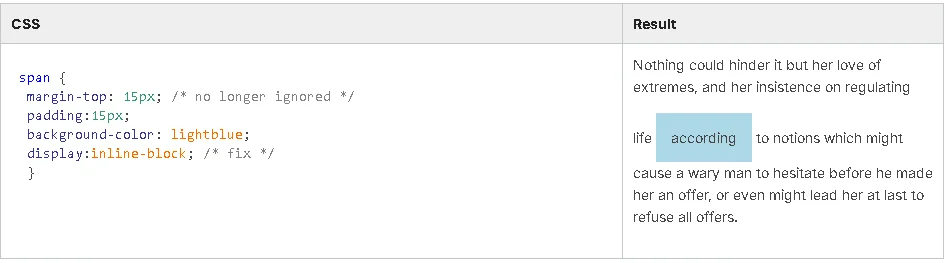

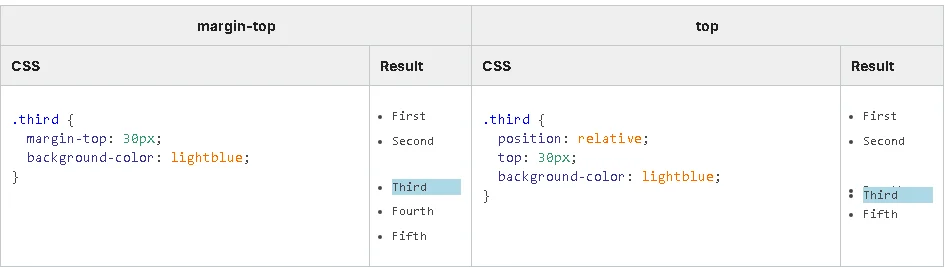

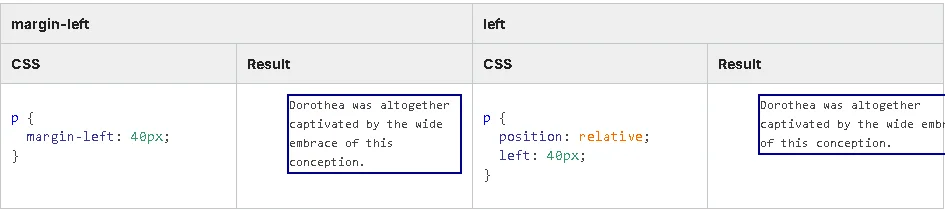

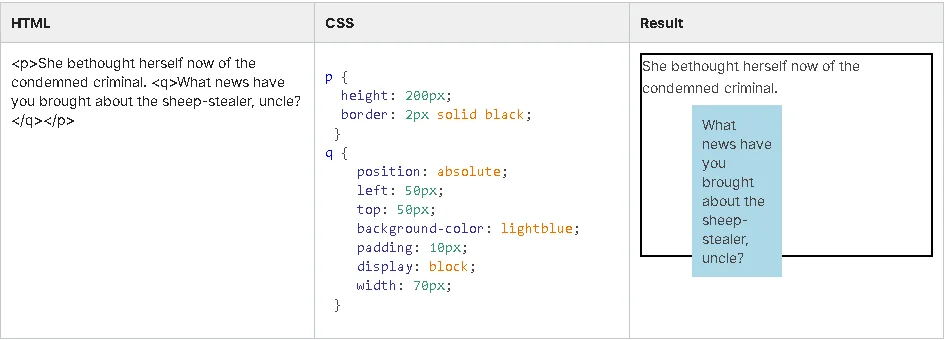

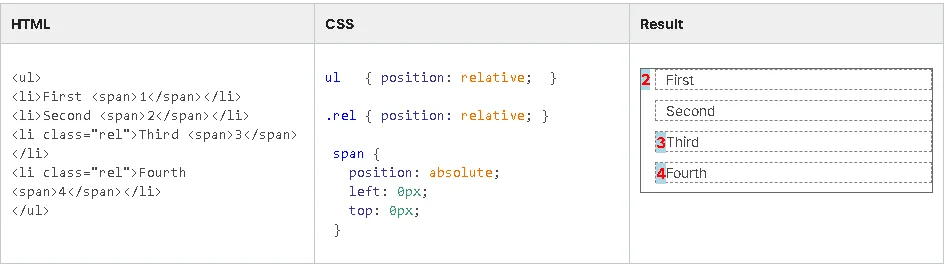

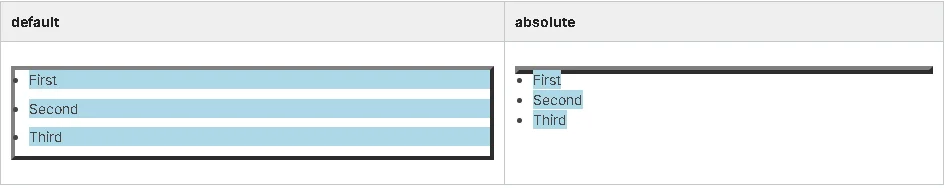

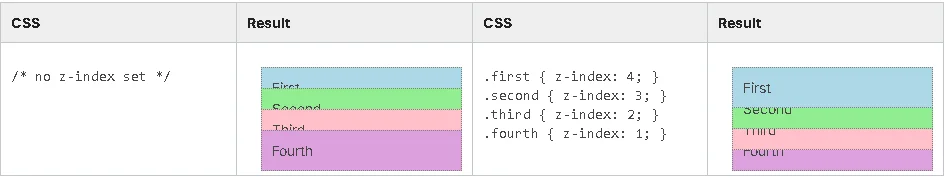

6.2 Concepts - text baseline and the display property

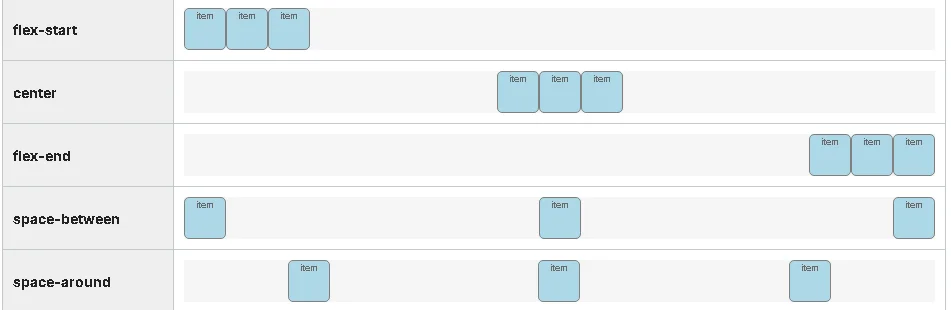

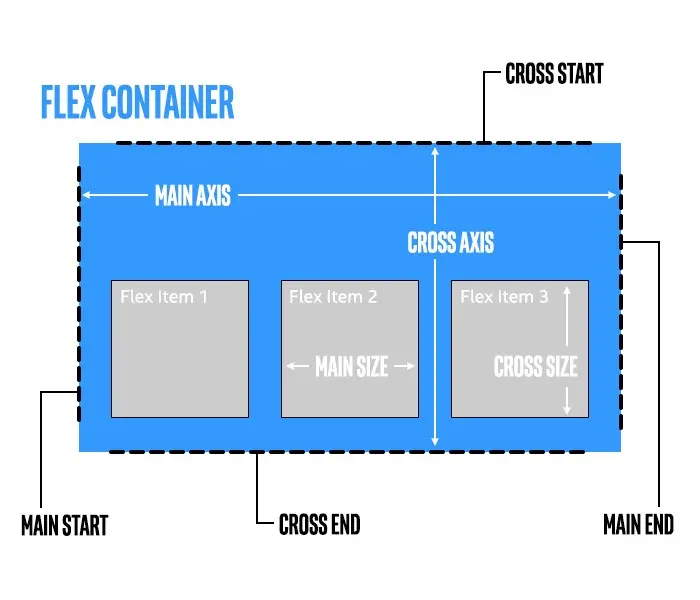

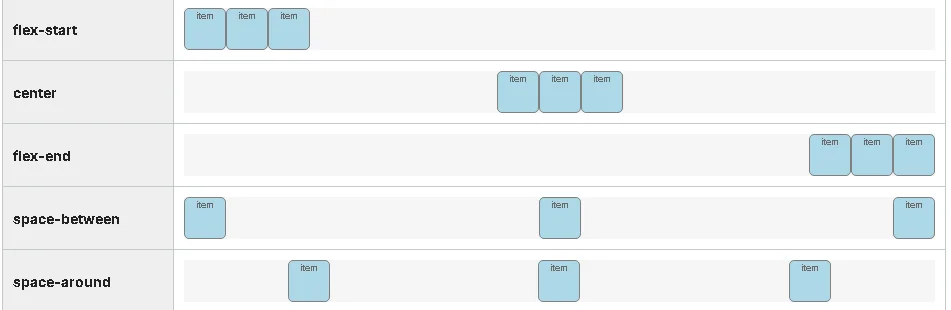

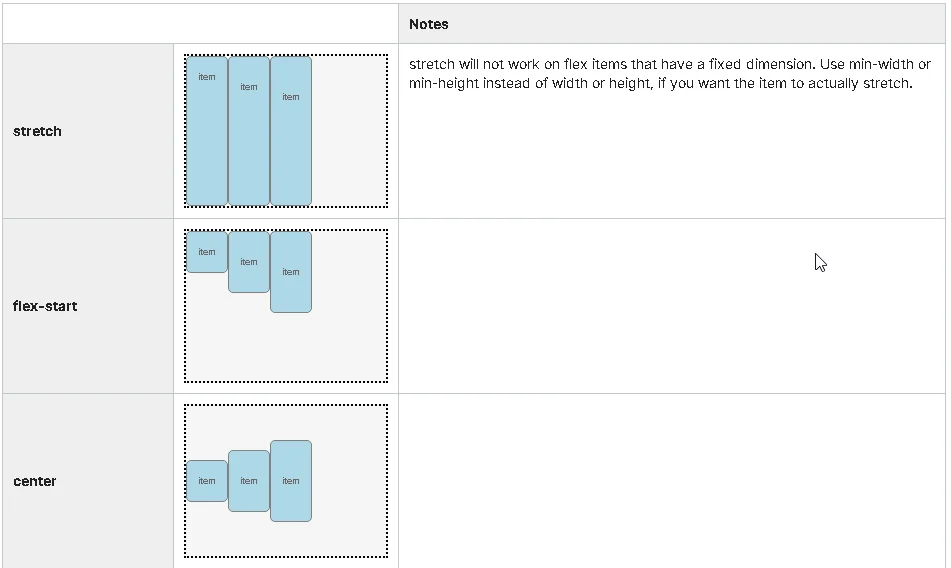

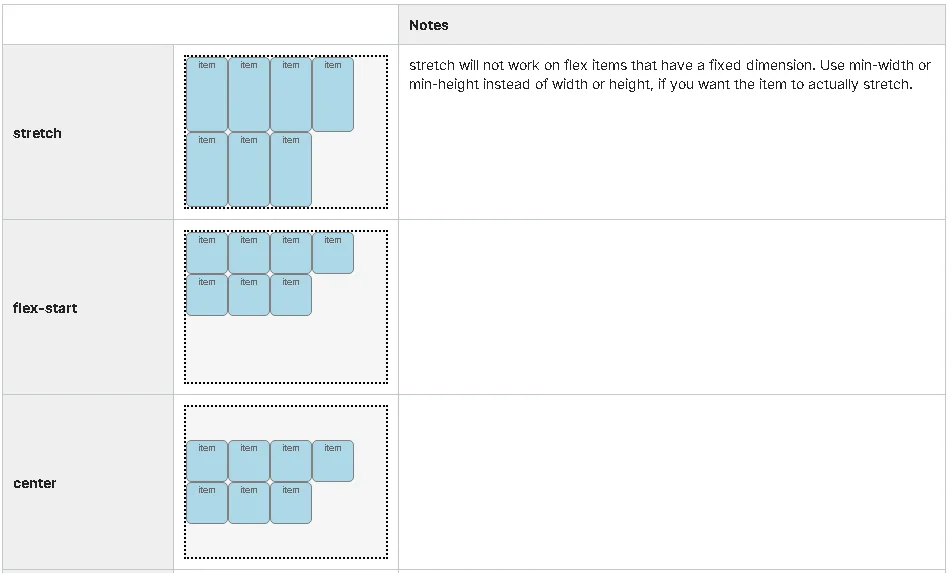

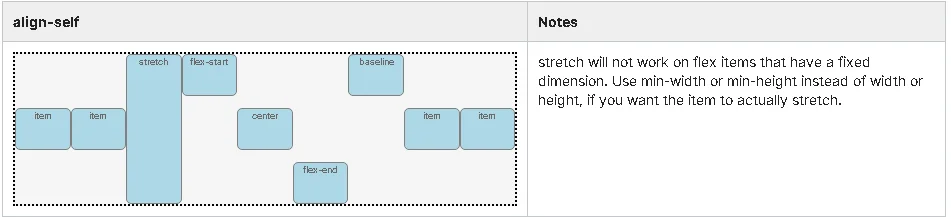

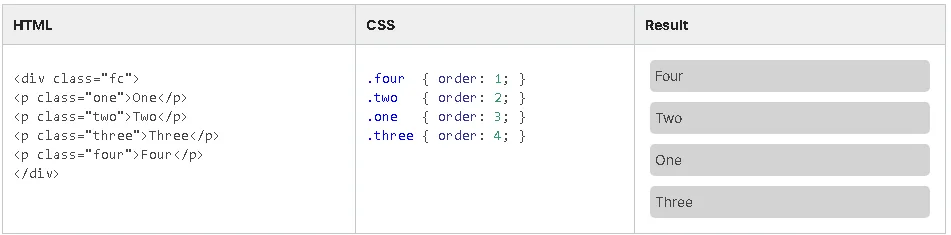

6.3 CSS Flexbox - sizing and dimensions

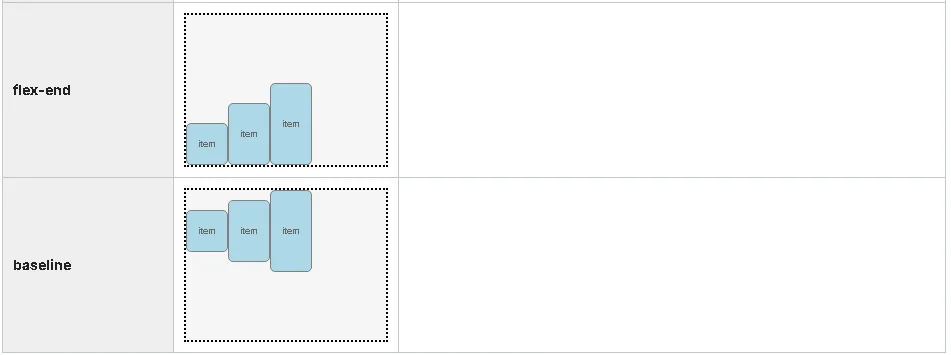

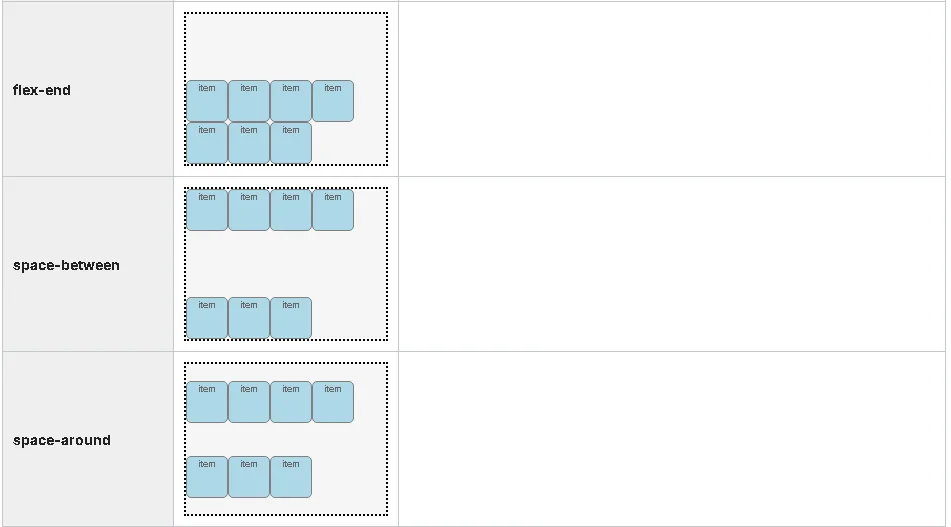

6.4 More Flexbox - main and cross axes

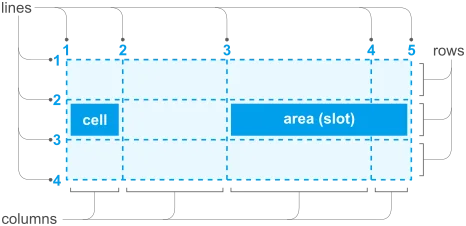

6.5 CSS Grid Layout

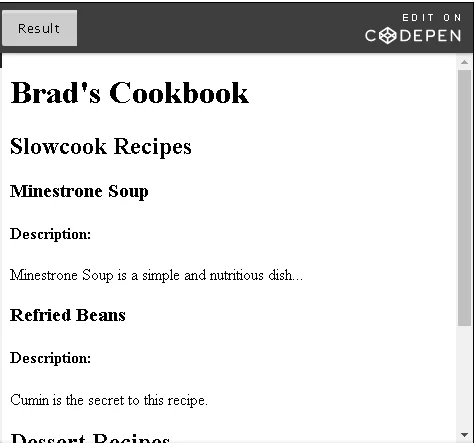

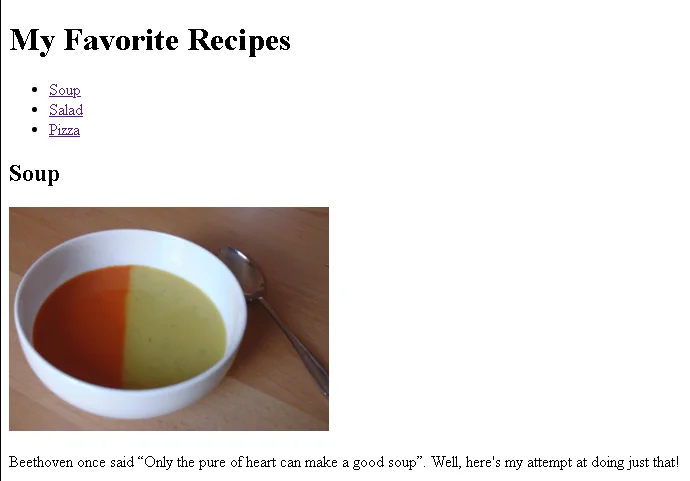

6.6 Recipe Project

Shall We? HTML5 and CSS Fundamentals - git

Quickly learn the basics of Web design and style to give your Web sites a professional look and feel, by just following these 6 modules!

It is how we determine the color, text size, spacing and other visual aspects of your Web page. We’ll introduce the syntax of CSS, how to include it with your pages, and get you started with some basic properties and concepts. Note that we’ll explore how to use CSS to layout your page during the last week of this course.

Whilst practicing and improving your recipe project (or else) with CSS features, you may have noticed that errors (subtle or not - we’ve all been there) can get in the way! This week you will learn how to fix your Web page when it’s not doing what you hoped it would do.

This is a good preparatory work for the HTML5 Coding Essentials and Best Practices course (#3) (intermediate level). You will also learn how to embed other elements in a page other than a simple image.

W3C has designed a “Front-End Web Developer” (FEWD) Professional Certificate where you will learn all of the necessary skills needed to build interactive and responsive user experiences on the Web.

This program will deepen your knowledge of the 3 foundational languages that power

the Web: HTML5, CSS and JavaScript.

The W3C FEWD program is composed of 5 courses:

This “HTML5 & CSS Fundamentals” introductory course is designed for anyone,

no prerequisites required.

During this course, you will learn:

Have fun!

Not surprisingly, it would be helpful to have a browser (short for “Web Browser”) so that you can see the end result of your source code. Common modern browsers for the desktop are Firefox, , Chrome, Microsoft Edge (pos) (and IE), Safari, , Brave, and Ecosia.

The most common features of a Web browser include the browser window itself (also referred to as the user interface), the navigation and address bar, and options to view your history, settings, and other tools. Look at the history of Web browsers (on Wikipedia). An interesting resource is the Browser and Platform Market Share (updated regularly).

An HTML editor is invaluable for both beginners and more advanced developers. While any text editor, like NotePad or TextEdit, can be used to create Web pages, they don’t necessarily offer options for error checking, syntax coloring and saving some typing by filling things out for you. There are two types of editors available, WYSIWYG (“What You See Is What You Get”) and textual HTML editors. Here is a non exhaustive list:

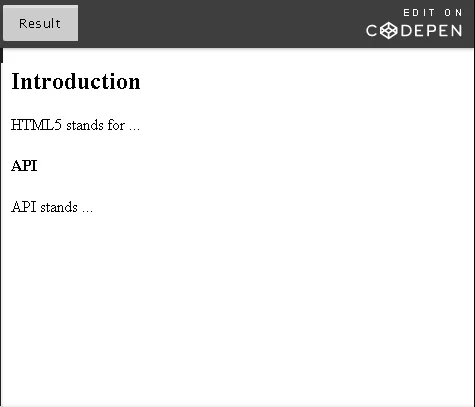

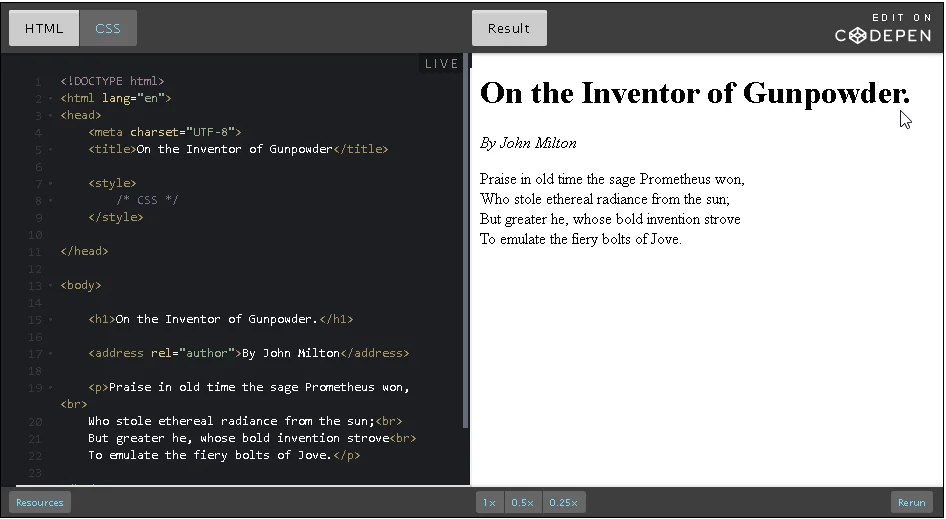

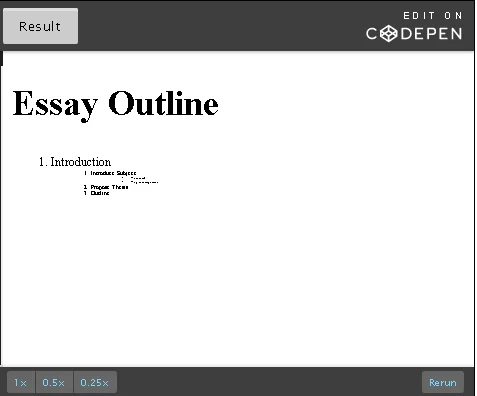

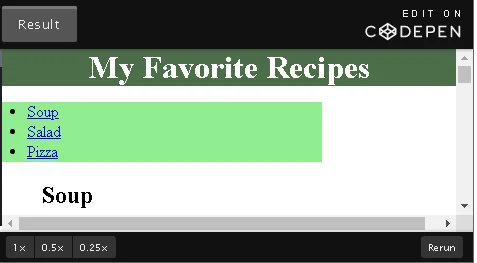

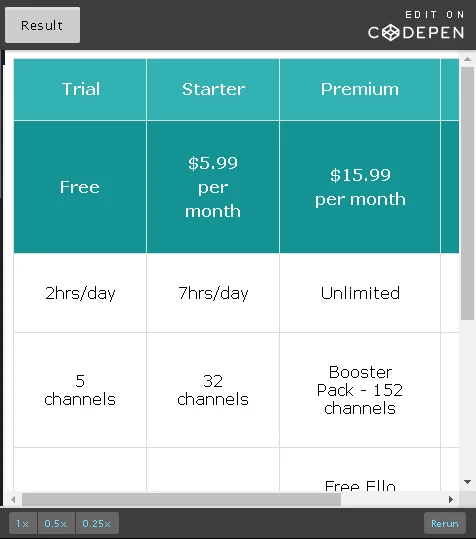

To help you practice during the whole duration of the course, we propose to use the CodePen online code editor. An online code editor is a tool that resides on a remote server and is accessible via browsers.

CodePen is an HTML/CSS/JavaScript code editor that previews/showcases your code in your browser. We are providing a short live coding video on how to use CodePen at the beginning of Module 1. CodePen gives you the tools for collaboration, experimentation, and sharing, but you also get live results and the ability to search through their database and repository of snippets that other authors put up so you can experiment and learn from their work, too.

Note that there are many other online code editors available out there, such as JSBin, JSFiddle, and Dabblet (Lea Verou’s tool). Here’s an interesting article on what beginners can do with CodePen: Things you can do with CodePen [Brent Miller, February 6, 2019].

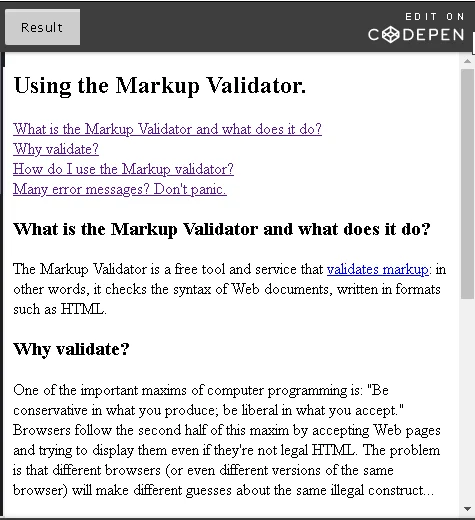

For over 15 years, the W3C has been developing and hosting free and open source tools used every day by millions of Web developers and Web designers. All the tools listed below are Web-based, and are available as downloadable sources or as free services on the W3C Developers tools.

The W3C Validator checks the Markup validity of various Web document formats, such as HTML. Note that you are automatically directed to the Nu Html Checker when validating an HTML5 document.

The CSS validator checks Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and (X)HTML documents that use CSS stylesheets.

Unicorn is W3C’s unified validator, which helps people improve the quality of their Web pages by performing a variety of checks. Unicorn gathers the results of the popular HTML and CSS validators, as well as other useful services, such as Internationalization, RSS/Atom feeds and http headers.

The W3C Internationalization Checker provides information about various internationalization-related aspects of your page, including the HTTP headers that affect it. It will also report a number of issues and offer advice about how to resolve them.

The W3C Link Checker looks for issues in links, anchors and referenced objects in a Web page, CSS style sheet, or recursively on a whole Web site. For best results, it is recommended to first ensure that the documents checked use valid (X)HTML Markup and CSS.

The W3C cheatsheet provides quick access to useful information from a variety of specifications published by W3C. It aims at giving in a very compact and mobile-friendly format a compilation of useful knowledge extracted from W3C specifications, completed by summaries of guidelines developed at W3C, in particular Web accessibility guidelines, the Mobile Web Best Practices, and a number of internationalization tips.

Its main feature is a lookup search box, where one can start typing a keyword and get a list of matching properties/elements/attributes/functions in the above-mentioned specifications, and further details on those when selecting the one of interest. The W3C cheatsheet is only available as a pure Web application.

The term browser compatibility refers to the ability of a given Web site to appear fully functional on the browsers available in the market. The most powerful aspect of the Web is what makes it so challenging to build for: its universality. When you create a Web site, you’re writing code that needs to be understood by many different browsers on different devices and operating systems!

To make the Web evolve in a sane and sustainable way for both users and developers, browser vendors work together to standardize new features, whether it’s a new HTML element, CSS property, or JavaScript API. But different vendors have different priorities, resources, and release cycles — so it’s very unlikely that a new feature will land on all the major browsers at once. As a Web developer, this is something you must consider if you’re relying on a feature to build your site.

We are then providing references to the browser support of HTML5 features presented in this course using 2 resources: Can I Use and [Mozilla Developer Network MDN Web Docs.

Can I Use provides up-to-date tables for support of front-end Web technologies on desktop and mobile Web browsers. Below is a snapshot of what information is given by CanIUse when searching for “CSS3 colors”.

To help developers make these decisions consciously rather than accidentally, MDN Web Docs provides browser compatibility tables in its documentation pages, so that when looking up a feature you’re considering for your project, you know exactly which browsers will support it.

W3C’s primary activity is to develop protocols and guidelines that ensure long-term growth for the Web. The widely adopted Web standards define key parts of what actually makes the World Wide Web work.

Tim Berners-Lee wrote a proposal in 1989 for a system called the World Wide Web. He then created the first Web browser, server, and Web page. He wrote the first specifications for URLs, HTTP, and HTML.

In October 1994, Tim Berners-Lee founded the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Laboratory for Computer Science [MIT/LCS] in collaboration with CERN, where the Web originated (see information on the original CERN Server), with support from DARPA and the European Commission.

And he did all this without becoming a multi-billionaire. Because he's a good human being. A good man. And above all, a code programmer. Otherwise, can you imagine the internet owned by the likes of Apple or Microsoft? That would be a fricking nightmare.

In April 1995, Inria became the first European W3C host, followed by Keio University of Japan (Shonan Fujisawa Campus) in Asia in 1996. In 2003, ERCIM took over the role of European W3C Host from Inria. In 2013, W3C announced Beihang University as the fourth Host.

As of April 2021, W3C:

Committed to core values of an open Web that promotes innovation, neutrality, and interoperability, W3C and its community are setting the vision and standards for the Web, ensuring the building blocks of the Web are open, accessible, secure, international and have been developed via the collaboration of global technical experts.

In the next video below, listen to what Sir Tim Berners-Lee said when asked what part of the W3C’s work he’s the most proud of.

People often use the words “Internet” and “Web” interchangeably, but this usage is technically incorrect.

The Web is an application of the Internet. The Web is the most popular way of accessing the Internet, but other applications of the Internet are e-mail and ftpfor example. One analogy equates the Internet to a road network where the Web is a car, the email is a bicycle, etc.

Read this article for more details about the difference between Internet and the Web.

Hello everyone! Welcome to Module 1 of the introduction to HTML5 and CSS course.

We have lots of exciting stuff to cover in this module, and we’re going to also create and edit our very first Web page. We’ll start with a brief history of HTML and the Web. Then we’ll learn how the big three, HTML5, CSS and JavaScript, relate to one another. We’re also going to learn about elements, tags, and attributes. We’ll cover best practices, some do’s and don’ts of writing HTML5.

As I mentioned already, throughout this module, you’ll have opportunities to practice what we’re teaching by creating and editing your very first Web page. With that, let’s jump right in.

1.1 Introduction: A video that introduces the content of Module 1.

1.2 The big three: Learn about the basic tools you will use to code for the Web including hypertext and Web browsers.

1.3 Elements, tags and attributes: Here you will begin learning about the functions of the different types of code.

1.4 Character encoding: To make you familiarized with international features.

1.5 Best practices, the wisdom: Studying other people’s mistakes is a great way to avoid the same pitfalls.

1.6 More on tags: Review of the tags we have just learned about and get started on your course project.

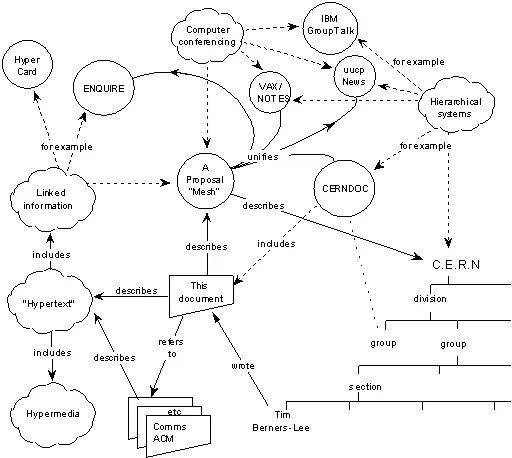

Over 30 years ago a proposal was sent internally at CERN outlying a universal linked information system. Dubbed ‘Information Management: A proposal’, pictured below, the proposal was created by Sir Tim Berners-Lee and was sent to his boss Mike Sendall, who described it as ‘vague but exciting’.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s vision for universality enabled the development of a high-level network of content that allows any document to link to any other documents.

The World Wide Web was initially created to make it easier to share research papers. It is a system of interlinked ‘hypertext’ documents that are accessed via the Internet; in essence, an information space. While he did not invent hypertext systems, Berners-Lee proposed using them ‘to link and access information of various kinds as a web of nodes in which the user can browse at will.’

His breakthrough was to link hypertext to the Internet and he used three technologies to do this:

In the following pages, we present HTML through what are usually called the big 3 (HTML5, CSS and JavaScript), the hypertext concept and the browser, an application program that provides a way to look at and interact with all the information on the World Wide Web.

When people say ‘HTML5’, they usually mean a bit more than just the 5th version of the “HyperText Markup Language”. Modern Web pages and Web applications are generally composed of at least three components, so what people often mean when they say ‘HTML5’ is the trio of languages: HTML5, CSS3 and JavaScript.

The ‘HTML’ part contains all the content, organized into a logical structure. This is the part that an author might be most concerned with: the words, chapter headings, figures, diagrams, etc.

While there have been numerous versions of HTML since its inception, our focus in this course is the most recent version, HTML5. HTML5 was developed to provide more powerful and flexible ways for developers to create dynamic Web pages.

The ‘CSS’ part (version 3 being current) is all about the presentation or style of the page; what it looks like without too much regard for the specific content. We’ll be going into more detail on that later in this course, but for now, think of it as the way you might specify a “theme” in a word processing document, setting fonts, sizes, indentations and whatever else may apply to what it looks like.

The ‘JavaScript’, or ‘JS’ for short, part is about the actions a page can take such as interaction with the user, and customizing and changing the page according to any number of parameters. This is what allows a Web page to be more than just a document, but potentially a Web application, with nearly unlimited possibilities. We will not be doing much with JavaScript in this course, but you should know that it is an important leg of the stool for modern Web pages.

A fundamental key to the World Wide Web is the concept of “Hypertext”. Hypertext is built on the idea of linking information together, not unlike using footnotes, except much easier and more flexible. The idea was to “Mark Up” your document with links and define how to break it down into different segments (chapters, sections, paragraphs, tables, figures, etc.)

That’s why, in 1989, Tim Berners-Lee began to create a definition of HTML: Hypertext Markup Language, to provide a simple, uniform way to incorporate Hyperlinks in a text document.

He envisioned a technology that would facilitate thoroughly interconnected documents. He wanted authors to be able to connect an idea in one document to the source of the idea in another, or connect a statement with the data that backs up that statement. Traditionally, this kind of thing was done with footnotes and bibliographies, which can be cumbersome. This information should be easily transferable from one place to another, so that in reading one document, it is easy to access everything related (linked) to it. Tim Berners-Lee imagined a “Web” of interconnected documents.

He used the metaphor of a Web to emphasize the importance of connections between documents. It was not just a long list of details, but rather a sea of information stretching out in all directions. This sea of information was navigated by a new tool called a “Browser”.

The Internet existed long before the Web came to fruition, and lots of organizations were connected to it, including schools, companies and government organizations. As things progressed through the 80s, the Internet was used for file transfers, newsgroups (a kind of open forum), email and other conveniences.

At the time there were a number of different programs like ‘fetch’, ‘gopher’ and ‘archie’ that were used to download, browse and search for files. Typically, you might use one tool to search for the location of files of interest, then another to copy that file to a local machine. Then, you still needed more tools to read that file. If it was text, you could use a text editor, if it was a formatted document you might need a word processor, if a picture you would need an image viewer and so on.

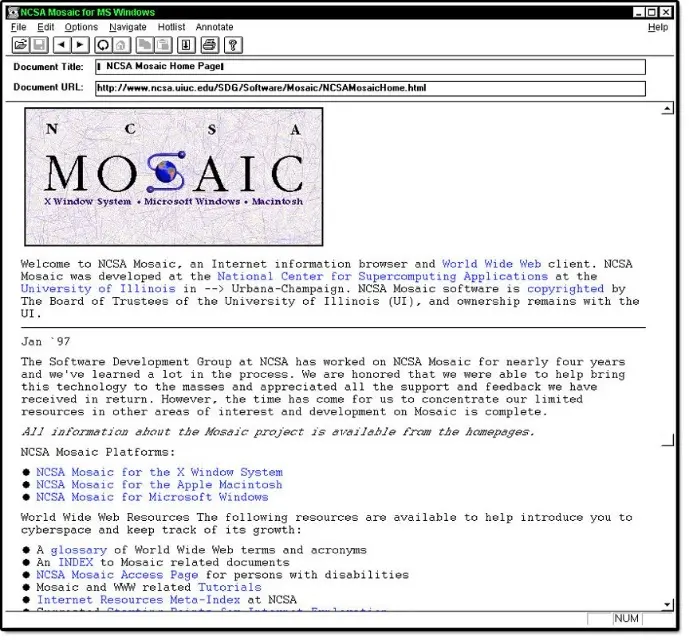

Marc Andreessen conceived of a solution that would put all the pieces together in one app, making it easy for users to browse all the different sorts of information and data on the World Wide Web. Together with others, he started the “Mosaic” project.

Though not technically the first browser, Mosaic was the first one that many people experienced and played a big part in popularizing the concepts of the World Wide Web and the Web browser. It provided a simple graphical way to access and browse the various resources on the Internet. Instead of using different tools to download and view information on the Internet, a simple click on a link would present the information in a graphical window. In many ways, it is the ancestor of most modern browsers.

The “M” in HTML stands for “Markup”, but what does Markup really mean? Essentially, it means to annotate a document with extra information. Things like where different sections and paragraphs begin and end, which part is the title, which things should be emphasized and so on.

There are many ways to markup a document, but HTML borrows a technique from an ancestor language, SGML (Standard Generalized Markup Language), which uses angle brackets (“<” and “>”) to separate the annotations from the regular text. In HTML these annotations are called “tags”. For example, consider the following chunk of HTML code:

<body>

<h1>A Tale of Two Cities</h1>

<p>

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, . . .

. . .

</p>

. . .

<p>

. . . it is a far, far better rest

that I go to than I have ever known.

</p>

</body>

If you eliminated everything in between the angle brackets from the text, for most purposes it would still read the same:

A Tale of Two Cities It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . . . . . . . . . it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.

Once you know that everything in angle brackets is “meta-information”, it leaves a lot of flexibility. You can put a lot of different things in between those brackets without any of it showing up (directly) in your finished document. And, though you don’t usually see directly what’s in those angle brackets, they can often have a big effect on what your Web page looks like as well as how it responds and interacts with you. Try It Out! I expect at this point you may be longing to write some HTML code. As is the tradition in programming tutorials, we’ll pause here to create a simple “Hello HTML” program. Please choose any Web editor of your liking (see in the subsection “Course tools”).

You can build and edit your HTML pages by either using online editors or editors that you can install on your machine, like Visual Studio Code.

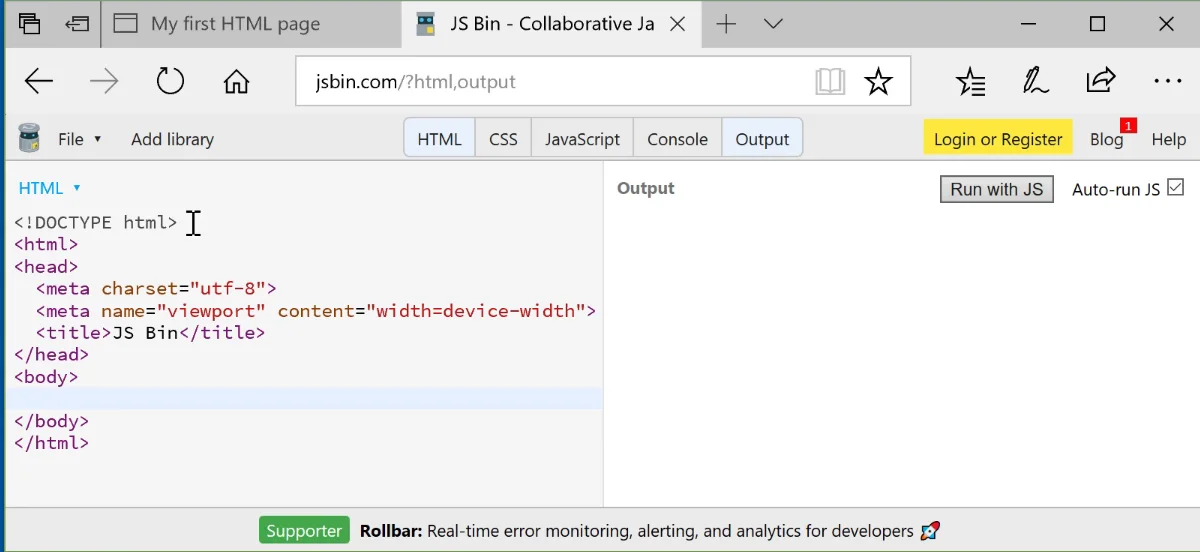

Both JSBin and CodePen are two online editors that you can use to create HTML Web pages. The following two videos show you how to create your first HTML page using JSBin and CodePen. And this time, what I’d like to show you a very simple HTML file that I’ve created. We’ll take a look at it in a browser, and then see how it’s built using a popular online HTML editor.

Here’s the file in question. It’s called hello.html. The .html extension tells me this is a HTML file, and it will contain some HTML code.

Let’s look at this file in a browser and by right clicking and saying open with Microsoft Edge. The file is loaded from my disk and then it displays its contents. And here you can see that this simple file, it is just showing me the text hello html and it’s also changed the title of the page to be my first HTML page.

There you have it, a very simple HTML page. Let’s now go to an online tool and try to create this page from scratch. How did we create this page?

Well, there are many ways to create HTML files and we’ll show you a few throughout this course. At this point in time, I’ll introduce you to JSBin, which is one of your options and to do that, I’ll open up a new tab and go to jsbin.com.

Here I am inside JSBin. You can see that I’m using the free version right now. I haven’t logged in, I haven’t registered it on anything else. I’m just going to use the site as a kind of HTML playground to create a simple HTML page.

We’ll have a quick look around the layout of the site. Here you can see there’s a panel on the left which is a HTML panel to edit HTML code, and on the right, you have an open panel that will eventually display whatever code you write on the left- hand side. And the site can cater for other languages such as JavaScript, CSS, and so on, and you can also share code snippets and do lots lots more.

I’d encourage you to browse around. But for this exercise, we’re just going to use the site in this simple format. As I said, this page on the left-hand side it was opened by default when we navigated here and it contained some HTML. There’s no content or output yet and we’ll get to that shortly. But this would be the most basic HTML code file that you would need to create in order to produce your first HTML page. You could probably do a little bit simpler but this is a very good template for us to start with.

Why don’t we just walk through some of the tags and elements that we see right in front of us. The first thing we see at the top of the page is a DOCTYPE declaration. This always comes before everything else in a HTML file. It’s actually just some information for the browser about what version of HTML the page is written in. And in this case here, it signifies that the page is written in HTML5.

The next tag we see is the html tag, and as you can see we have the beginning tag here and the ending tag at the end, which means everything on a HTML page is contained within these two tags.

All other tags must be contained or nested within this tag, and it tells the browser of course that this is a HTML document.

In this example, we then have a head tag, again the beginning and end, head tag, and as you can see, this head tag contains other types of elements. You can see in this example there’s a meta and a title element, and there are more than these two. We’ve actually seen the title element in action already. It defines the title for the page, that’s used in the browser tabs or toolbar and the title is also used in the browser history.

For example, in our page we had typed: “my first HTML page”, and that’s where that would be created. That’s the head tag. <head>

Next up is the body element. <body> And as its name suggests, this element contains the body of the page, meaning all of its contents. As you learn more and more about HTML you’ll see there’s lots of different tags you can put in here to do various different things within your HTML page, but for now as in our example, we’ll just type some text.

Hello HTML!

And as you can see, output is now appearing because we have some content in our body. And I can do a lot more here if I want to, but for now that’s just showing you that this page has created the same output as our original page “Hello HTML!”, and the page title we’ve said is my first HTML page, and that’s the amount of code it takes to construct that page.

Hello, everyone. Today, I’d like to give you a brief overview of a site called CodePen. I’m already at the site here in my browser at codepen.io, so you should browse there, too. And here I am at the landing page and I haven’t logged in, I don’t have an account.

What I’m going to show you now is just a very brief overview of what the site can be used for. A “Pen” in this site is kind of like a Code snippet. It’s code you can write, or you can also explore Pens that the community has put up on the site for you to consume.

Let’s start there, let’s have a look at what a Pen might look like. To do that, I’m going over here on the top right to the “Search” button, and I get a nice big Search text box. And if I just type in a term that I’m interested in, for example, “Button”, and I just wait a brief second, you’ll see that that search returns 936,000 Pens.

These are pieces of code that other people have shared that contain something to do with Buttons, the key word “Button”. This is the list that you’ll get back and you can explore and do a lot of configurations on the search.

To see the code behind one of these, you would click on the Tile that has been returned. And I’ll do it, I’ll click on this one. And you can see an “Editor” opens up, and it has a HTML Pane, A CSS Pane, a JavaScript Pane, and an Output Pane. This is just an example.

We won’t go into the code in this example. But you can see that this is a live preview of what’s being shown here from the code out down here below in the Output window. Let’s go back. That was just an example of a Pen that someone else has created and they’ve decided to share it publicly. Why don’t we try and create our first Pen?

To do that, we’re going to come over to the “Create” button here. Click on “New Pen”. And you’ll notice I still haven’t logged in. I’m just using the site as a public visitor. I click on “New Pen” and an empty editor opens up.

You can see the three panes HTML, CSS and JavaScript. Nice big output panel here down in the bottom. Don’t like this view? Go ahead and “Change view”, and you can reconfigure it to have editors on the left, the editors on the right, et cetera. Now, I’ll just stick to the “Default view”. Also, only going to code some HTML, so here, I’m going to “Maximize the HTML editor” which slides the others out of view of a nice lot of space here to work with.

To save some time, let’s just paste in some HTML. What you see here is that the preview is live, as in, when I make a change in my code, it shows up in the output practically instantaneously, which is a really great feature. Let’s change the code to watch it in action. I’m going to change my code “Hello CodePen!”. I’m going to wrap it in a header, H1 header, and we should see that text get larger in the output panel. I put in my tag, and you can see that it’s actually expanded which is great.

The other nifty little features that you can use here:

If you get HTML into a state you’re not happy with how it looks on the screen, you can say “Tidy HTML”. And we’ll try to indent a little bit better and spread it out so that it’s more readable. Even go as far as going into the “Settings” and under “Behavior”, use “Tabs” over “Spaces”. That’s a nice feature.

That’s the code editing part of CodePen. And I encourage you, if you don’t want to download a tool or other editors, you can browse here for free and write some code and see it appear in the Output window.

Take other people’s code and play with it. Explore with their cool creations and try that stuff out as well. Another reason I wanted to introduce CodePen is, because if you look at our course, you may come across this editor here in line, inside the content that we’ve created.

It’s an embedded CodePen editor. In this example, it shows you two panes, the “HTML” code and the “Result”. Switch off the “Result”and just show the “HTML” by clicking on the “Result” button. Vice versa. I can also edit inline here. For example, if I go into this paragraph in code and I say something like “Hi!”, that will refresh, on the right hand side, the actual output, which is interesting.

I’ll just ignore that DOCTYPE warning for the moment. That’s not really important right now. This is a live editing experience embedded into our course, but you can go over to CodePen which is where we’ve been, and you can navigate to the actual Pen that was created. And here, you can see that in the CodePen site. And you get yourself an account on CodePen.

You’re able to do stuff like just fork this, which is effectively copying this actual Pen into your own account so you can play with it, use it, and so on, and so forth. That’s the round tripping. I just wanted to make sure you see. When you come across these integers inside our course, you’ll know that that’s really a CodePen editor inside the content, that you can then go and use the CodePen site, or use it directly inside the content itself.

So that’s it. A very quick look at the popular online editor and front-end code playground called CodePen. Until next time, happy coding.

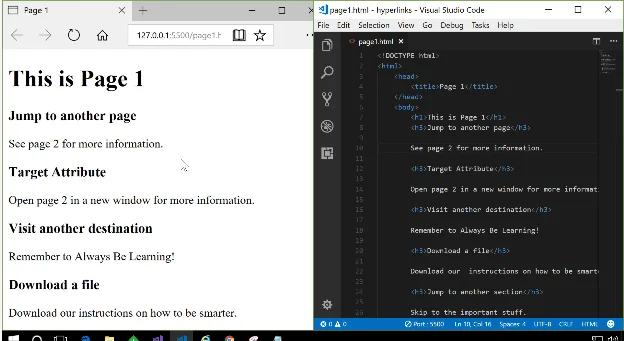

Watch these 3 demos/videos below to learn how to use Visual Studio Code (VS):

To get Visual Studio on your machine, simply visit cpde/visualstudio.com.

Visual Studio Code is a very powerful and popular code editor. It’s completely free and it supports a multitude of programming languages. And as you can see here, it’s also available for multiple platforms, Mac OS, Windows and Linux. One of the really great things about this editor is that it’s open source and has a very active community behind it. And that means that great features and fixes are released every month.

If I scroll to the end of this page, I can see that the number of stars in GitHub, which is basically the number of people who have showed appreciation or liked this editor, is quite high. There’s a lot of activity behind this editor. Once you follow the installation instructions for your platform, and you have Visual Studio Code on your machine, launch it.

On this Windows machine, I’ll just click on my Visual Studio Code icon, and then a couple of seconds (or minutes), Visual Studio Code will be launched. You should be presented with a similar welcome screen when you open Visual Studio Code for the first time. To get going here, what I’d like to do next is open a file or create a new file. And I can do that here by clicking on “New file”, or up in the main menu by choosing “File”, “New File”, or even using a shortcut.

For now, I just click on “New File” and I’m presented with this new file inside the code editor. I’ll just paste some HTML in to save some time. And there’s some HTML and so far, nothing too exciting. What we have to do next is help the editor realize that this is HTML. And we do that by naming this file with the HTML extension. I’ll save the file and save it off to my disc. And let me see…

HTML and I’ll call this one test.html Bingo. Once you do that, you can see that the editor has recognized this page as HTML and it’s beginning to light up the content. You can see the nice color coding of the page we get for free out of the box.

Let’s look at a couple more things we get with this basic support for HTML. If I move my mouse over any tag, I get more information on the symbol under the cursor. If I roll over HTML, I get some information about that tag and similarly for the body tag and every other tag or element on this page. This is great when you’re learning the language. If I’m inside my page and I’m editing, if I open an angle bracket, it gives me a list of possible tags I can use. And if I select the tags, for example, P, and I close it with an angle bracket, the editor automatically inserts the end tag if one is needed for that particular element, which is really useful, too.

There are two more things I can use. Another one is if I’m in my HTML or any other code inside a Visual Studio, and I want to tidy it up a bit, one thing to try is “shift-Alt-F”, and it will prettify or beautify the page a little bit. And that’s useful. And on the MAC, you can use the same command, “Command K”, “Command F”.

That’s just a couple of more features that are available out of the box in Visual Studio Code for HTML editing. Of course, it’s always nice to see what your HTML code looks like when the page is rendered in a browser. One way to do that is to open the file from the local folder. If I go to my Windows Explorer, and I have my file test.html, I can right click on it and say “Open with” and choose a browser.

And as I’ve done before, I’ll choose Microsoft Edge (which is a POS). And there is that file rendered inside the browser. Unfortunately, there is no preview in browser function available by default in Visual Studio Code. Fear not, community to the rescue. As I mentioned earlier, there’s a vibrant developer community around this product. And they fill in feature gaps when needed.

Visual Studio Code has hundreds of extensions available in the Visual Studio Code marketplace.

Let’s find an extension to help us preview our HTML in a browser. There are many ways to get to the Visual Studio Code extensions marketplace.

One way is to come up here to the “View” menu and select “View Extensions”. And a panel is opened beside the editor which will allow us to search for extensions in the marketplace.

Here, I’ll type in the word “browser”.

And we’ll get a lot of different extensions related to browser listed here. I encourage you to look through some of these, look at the ratings and figure out for yourself which extensions you’d like to install. I’ll try this open in browser because I think this is one I’ve already installed previously.

Just for demo purposes, I’ll install that. And you can see it says installing, and then reload. I have to click reload to activate this particular extension. This only takes a couple of moments. And once it’s installed, then I have to go back into my HTML. I can see in the extensions panel here that it says it’s installed which is great. And I believe the command to preview using this extension is “control-K” and then “D’. And as you can see, it launches my default browser. And it shows me the preview of that page.

If I go back to my Visual Studio Code and I changed this to be VS code and I save it and I say “control-K-D”. There you go. It previews. That’s just an example of extension we can use in order to preview our HTML code in a browser from Visual Studio Code.

That’s it. That’s a quick lap around Visual Studio Code for HTML editing. And I encourage you to explore the documentation and discover more features of Visual Studio Code.

In this module, I want to show you options in Visual Studio Code for preview in HTML in a browser.

By default, Visual Studio Code gives you very little help out of the box. What does that mean? Well, take this simple page, hello.html…If you want see it in a browser, there are no default commands in Visual Studio Code to help. Instead, I have to locate the file on my disk, and use my operating system menu commands to open it in a browser like so.

That’s my first option to preview my HTML, and it may be enough for very small projects.

Given that I know the format of the address to type into the browser, I can load other pages as well.

For example, if I change hello.html to images.html, I can load a different page. But let’s go back to our original page. The limitations of this preview approach are twofold.

As you saw, I have to load the page manually the first time. And when I make changes to the file, I’m going to have to remember to save the file and refresh the page in the browser. I show you what I mean. If I put my file to the side and put my visual studio code here, if I change my file and say “Hello Demo!”, you can see the file has to be saved.

If I save my file, you notice my browser doesn’t change. Instead, I have to also remember to hit refresh. This two-step approach, and therefore, this way to preview my HTML is still pretty cumbersome. Let’s improve upon the situation with the power of Visual Studio Code extensions.

As you may recall, you can access the extensions through the view extensions menu command. Here, the extensions marketplace is opened up, and just make sure we have enough room to show this. Then the search box, I’ll type browser in to have a look at some of the extensions that contain the word browser. And as always, I encourage you to do your own research, review ratings and reviews, to determine which extensions are best for you to install.

I’m just showing you examples here and I’m not endorsing any particular extension that I’m showing in this demo. That said, in order to show the demo, I’ll choose one of these first three open in browser type extensions. I’ve worked with this one before, open-in-browser, so I click “Install”. And as you can see, that has installed. I need to reload my work space in order to have that extension be activated.

Let’s use this extension to see how we can open the HTML page I have in front of me into a browser. This extension has two commands. One is the Ctrl+Alt+O command, which allows you to select a browser in order to open this page in.

I won’t do that for now because the other ways open your default browser, which is Ctrl+K+D. And as you can see, that’s opened a copy of Microsoft Edge because that’s my default browser, and it’s launched my page. If I now expand the explorer panel in my editor,

I can right click on any HTML page, and now I have an open in default browser selection. Here, I’ll open the images page just here. I’ll open that just with a command inside Visual Studio. With this extension, I remove the task of finding my file on disk and using the context menu to load it. I also don’t have to remember addresses for files. An extension like this is definitely a step forward. However, to view my changes, I still have to save my file and reload it in the browser manually.

If I type in “Hello Demo2!” and I save my file, you can see, there is still no change.

I have to refresh my page here.

The next level of HTML preview extension you can install is one that offers a live preview.

A live preview of a HTML page is when your page is actually loaded into a local Web server running on your machine. And so the pages live, meaning any changes that you make to the page, also show up immediately on the page and in a browser. I’ll show you how you can do that right now. First of all, let’s go back to “Extensions” panel.

And here, I’m going to search for something like, “Live Preview”, and let’s see what comes up there. I’ll just expand this a little bit. These first few extensions look interesting here from a live preview perspective.

The first one, “Live Server”, will actually launch a development local server and load the page into it. I’ll try that one out. I’ll just click install. And as you can see, it installs pretty fast. I like that run. Now that that’s installed, I have to reload this workspace in order to activate that extension. Now we have our new live server extension in place.

Down below, we see that there is a live server button called “Go Live” that this extension has installed. And if I click on that button, it will start a server port 5500. I’ll Just close that. And over here on the browser, you can see it’s actually launched that server at this particular address with my page that I have opened. What does that mean to me? Well, it means that if I was to change my HTML text again, and I haven’t saved if I do file, save. I’d just watch the browser on the left-hand side. As soon as I hit “Save”, the live server to text those changes and service the page to me again.

That was a quick roundup of some options to make your HTML preview experience better in Visual Studio Code. In this exercise, we’re going to build our first Web page from scratch using Visual Studio Code.

As you can see, I have Visual Studio Code open, and so the first thing we want to do is create a blank HTML page. I’ll do that by choosing “New File”. I have a new file now but I need to save it as a HTML file. I’ll say “Save As”, and I’ll use the file name: index.html.

And now the editors recognize this as a HTML file. Let’s see what that looks like in our browser. The file is saved. I’ll go to my “Local Disk”. I’ll select the file and open with my browser, and as you can see it’s blank. Tt is picking up the file from my “Local Disk”, index.html. It’s just a file that has no contents.

I’ll just leave the site by side with Visual Studio Code so we can see everything together once. There you go. Now we’re ready to add some HTML to our file.

The first thing we need in our file is the DTD tag or the document type declaration. And as you recall, what this does is this information for the browser to tell it what version of HTML we’re running. And in our case, this is HTML5 represented by the value html.

Great. Now the next thing we need to add is the html element and that takes up the rest of the files, meaning that everything else we add after this will be contained within the HTML element. We still don’t have anything visible on the page. As you can see here, when I refresh my browser, it’s still empty, because we have no content yet over here on our HTML page.

Let’s move on. The HTML element typically has two children. The first one is the “head” element, and that’s typically followed by the “body” element. The “head” element contains mostly data that isn’t visible to the user, sometimes we call that metadata. However, there is one exception to this and that is the element called “title”. And this is an element that has content that will be visible to the user.

If I use, if I put in a title element and inside it, I add some content, “My First Page”, for example. If I save my page now and then refresh over in the browser, you will see that that content, “My First Page”, it shows up as the title of this page inside the browser. And that title is also used for indexing and for Web browser history, and so on. That’s the name of the page that will show up.

That’s a visible element that’s inside “head”. Okay, let’s add some content to the page body. In between the “body” element, I’ll just add some text, and if I save my page and refresh my browser once more, we’ll see my text up here has shown up. And we can do lots more inside this “body”. For example, if I was to change this so that, let’s add another tag…Use one of the HTML headings tags, and if I save my file and refresh again, you can see how that text changes its look based on the tags that enclose it. And HTML5 defines multiple heading tags.

I’ll try another one. There’s another one, and when I save it and refresh, you can see the different sizes.

That’s it. We have our first Web page built from scratch. We defined a “title” here which showed up here. And we also defined content in the “body” of our page which shows up like this, based on the various tags that we’ve used. Now we have only used a tiny fraction of the HTML elements and tags that are available to you. But hopefully this shows you, just how easy it is to get started.

If you are sitting at a coffee shop next to a table of Web developers, you will probably hear three words quite a bit: ‘Tags’, ‘Attributes’ and ‘Elements’ (or sometimes ‘DOM elements’, same thing just more precise and wordy).

‘Elements’ are the pieces themselves, i.e. a paragraph is an element, or a header is an element, even the body is an element. Most elements can contain other elements, as the body element would contain header elements, paragraph elements, in fact pretty much all of the visible elements of the DOM.

Consider the figure above. It contains a single ‘html’ element. It turns out this includes within it the entire content of your html file. If you click on the “html” node, you’ll find that it contains two components, a head and a body. Clicking on each of those will reveal their respective contents. This structure is what we computer scientists call a “tree”. Any given element (except for the outermost ‘html’ element) is wholly contained inside another element, referred to as the “parent” element. Not surprisingly, the elements that a given element contains are its “child” elements. And, yes, children of a common parent are often referred to as “siblings”.

Thus, in the example above, the top element is the html element, which contains just two elements, the head and body. The head element contains a title element and the body contains an ‘h1’ element and a ‘p’ element. In a more typical example, the body would contain many more children, but for our purpose this is enough.

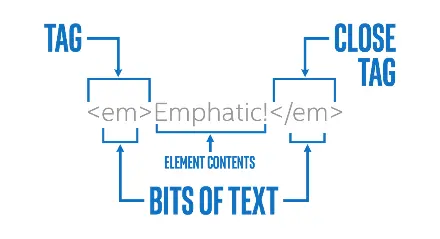

That may be a great picture, but how do we represent such a structure in a text file? Well, that’s where “tags” come in.

‘Tags’ are what we use to organize a text file (which is just a long string of characters) such that it represents a tree of elements that make up the html document. Tags are not the elements themselves, rather they’re the bits of text you use to tell the computer where an element begins and ends. When you ‘mark up’ a document, you generally don’t want those extra notes that are not really part of the text to be presented to the reader. HTML borrows a technique from another language, SGML, to provide an easy way for a computer to determine which parts are “MarkUp” and which parts are the content. By using ‘<’ and ‘>’ as a kind of parentheses, HTML can indicate the beginning and end of a tag, i.e. the presence of ‘<’ tells the browser ‘this next bit is markup, pay attention’.

Whatever that tag (or ‘open tag’) does, it applies to the content following the tag. Unless you want that to be the entire rest of the document, you need to indicate when to stop using that tag and do something else, so ‘<’ and ‘>’ are again used. Since elements are typically nested within other elements, the browser needs to be able to distinguish between the end of the current tag or the beginning of a new tag (representing a nested element). This is done by adding a ‘/’ right after the ‘<’ to indicated that it’s a ‘close tag’. To indicate the beginning and end of a paragraph (indicated by the single letter ‘p’) you end up with something like this:

<p>This is my first paragraph!</p>

The browser sees the letters ‘<p>’ and decides ‘A new paragraph is starting, I’d better start a new line and maybe indent it’.

Then when it sees (xyz) it knows that the paragraph it was working on is finished, so it should break the line there before going on to whatever is next.

For example, the ‘<em>’ tag is used for element that needs Emphasis.

The ‘<’ and ‘>’ indicate that this is a tag, and the “little bits of text” in between tell us what kind of tag it is.

To completely describe the element, it needs an open and close tag, with everything in between the tags being the content of the element:

Most tags have open and close versions, but there are a few strange ones.

We’ll learn more about these later, but we generally refer to the strange ones as “self closing” tags.

Usually these tags represent an element that is completely described by its attributes, and thus there is no need for other content.

So if you see something like this:

<img src="https://goo.gl/pVxY0e" alt="Floating flower"/>

… then you should know that the slash at the end of the open tag is sort of a shorthand for a close tag, so you won’t see any other indication that this element is now complete.

There are also a few tags that don’t even use the ‘/’ at the end, they just don’t have any close tag at all.

This works because all of the information this tag needs is declared in an “attribute”.

Computers are great at reading computer languages, but it’s not always easy for humans. Comments are a way of adding some text that is primarily targeted towards human readers.

Every programming language I’ve used has some way of representing comments. HTML5 is no exception. If you want to add something in your file that you want the browser to completely ignore, there’s a special tag for that (unsurprisingly called a “comment tag”):

<!-- This is a comment -->

An HTML comment tag starts with , meaning that as the computer is reading through your HTML file, if it sees . There is no open or close tag, just a comment tag. Unlike most other things in HTML5, comments cannot be nested. If you try that, like:

<!--

Beginning of comment

<!-- comment nested inside -->

This is after the nested comment

-->

The computer will then see the beginning of the comment tag and start ignoring everything until it sees –>, including the second , it assumes the comment is done and goes back to processing everything it sees as HTML code and content, even though the writer may have meant it to be a comment.

Like most other tags, it can span multiple lines of your source file. This can be really convenient when you have a lot to say:

<!-- If you want some good advice, Neither a borrower nor a lender be, For loan oft loses both itself and friend, And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry. -->

Comments are also commonly used in development to block out bits of code, whether for testing or leaving unfinished business in the file:

<!-- Not sure if I want this wording or not:

<p>Eighty seven years ago, a bunch of guys started a new

country</p>

-->

It’s important to remember that just as HTML, CSS and JavaScript are three different languages, they each have their own notation for handling comments.

This might seem confusing, but it’s actually kind of important that the HTML comment notation, at least, differs from the others.

As for the exact form of those comments, we’ll cover that in good time.

Most of what we’ll cover about attributes will come later, but I wanted to introduce the idea briefly. Basically, a given element on your Web page can be distinguished by any number of unique or common attributes. You can identify it uniquely with an ‘id’ attribute, or group it with a class of other elements by setting the ‘class’ attribute.

Attributes in HTML are written inside the opening tag like this:

<p id="paragraph-1" class="regular-paragraphs"> Call me Ishmael . . . </p>

The paragraph above has a unique identifier, “paragraph-1” and is part of a class of “regular-paragraphs”.

The letters inside the quotes have no meaning to the browser, they just need to be consistent.

They are actually strings (of characters), which, as we will soon learn, suggest that if you want to have another paragraph in this class, it has to say “regular-paragraphs”, not “regular” or “Regular-Paragraphs” or any other variation.

Again, the fact that the computer does not care what we put in those strings (except for some restrictions) means we can use them to convey meaning to a human developer.

I could just as easily have said id=‘x’ and class=‘y’, but anyone looking at that would have no hint what the significance of x and y are.

Best practice is to name these things to increase clarity, consistency and brevity.

But more about attributes in the next module.

One key to understanding HTML, or any computer language, is to be sure that you avoid ambiguity, because computers generally are not good at judgement calls.

For example, you could streamline HTML so that whenever you see a <p> tag, you start a new paragraph, no close tag needed.

That might work most of the time, but that would prevent you from nesting one element inside another, as the browser could not know if you meant the new element to be nested or a successor.

A human designer might be able to tell what you meant from the context, and knowing that mistakes happen choose the one she thinks is best suited in that case.

A browser, on the other hand, has difficulty with a task like that, so it is helpful to use a close tag that matches the open tag to make things absolutely clear.

<p> The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them. There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in time to seize a small boy by the slack of his roundabout and arrest his flight. </p>

The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them.

There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in time to seize a small boy by the slack of his roundabout and arrest his flight.

A human reader could easily detect that two paragraphs were intended and that the writer probably just forgot to terminate one and start the other. The browser, on the other hand, will only see one paragraph and layout accordingly.

On the other hand, you might think that since a browser always knows exactly what tag it is working with (eidetic memory), you could provide a sort of “universal close tag” that doesn’t specify the type that it’s closing. It would know to close the current tag. While that’s technically true, it’s handy to have the close tag there for people reading the code. The close tag makes it easier to remember what tag it is closing. We humans can get confused trying to remember that kind of detail.

But there are other ambiguities to consider. For example, when a browser receives a file, it may know that it’s receiving an HTML file, but it won’t know which version of HTML is used (it matters).

That’s why the first thing you need in any HTML file is a tag to tell you what type of HTML file it is:

<!DOCTYPE html>

In other words, the first thing the browser sees is the declaration “This is an HTML5 file, in case you were wondering”.

It may seem tedious to put this at the top of every file, but believe me, it used to be worse.

You probably noticed that it doesn’t say “!DOCTYPE HTML5” but just “html”.

HTML5 can do this because all the previous versions were much more long winded.

For example, at the top of an HTML 4.01 page, you might have something like this:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

We do not need to go into the details of why and what that means, just be grateful that HTML5 did away with it.

It may seem redundant, but the next bit tells the browser where the actual HTML code begins, using an <html> tag:

<html>

Nearly every HTML document has two parts. The body is the main content of the page, containing text, images, tables and so on.

The head comes before the body (on top?). It is where you put information about the document that does not really go in the body, AKA ‘meta-’ information. Things like what kind of character set the page is using, where the browser can find style tips, and what the title of the page is (which might be different from the title the user reads) all go in the <head>.

If you have been paying attention, you should be able to create a very basic html file, in the right form, without any content.

Hint, for the head of the document you would write:

<head> </head>

You may recall the paragraph tag <p> that we used in the example above. Try inserting a paragraph into the body of your new document. You should end up with something that looks like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<p>

As my English teacher used to say, 'One sentence does not a

paragraph make'!

</p>

</body>

</html>

A character can be any letter, digit or symbol that makes up words and languages.

English alphabets and digits ‘a-z’, ‘A-Z’, ‘0-9’ are all considered characters.

Other examples of characters include the Latin letter á or the Chinese ideograph 請 or the Devanagari character ह. A character set is a collection of characters (letters and symbols) in a writing system.

Each character is assigned a particular number called a code point. These code points are stored in computer memory in the form of bytes (a unit of data in computer memory). In technical terms, we say the character is encoded using one or more bytes.

Basically, all the characters are stored in computer language and a character encoding is the awesome dictionary that is going to help us decode this computer language into something we can understand.

In technical terms, it is what is used as a reference to map code points into bytes to store in computer memory; then when you use a character in your HTML, the bytes are read back into code points using the character encoding as a reference.

When you code in HTML, you must specify the encoding you wish your page to use. Providing no encoding or the wrong one is pretty much like providing the wrong dictionary to decode. It can display your text incorrectly or cause your data to not be read correctly by a search engine.

A character encoding declaration in your HTML is also important to process unfamiliar characters entered in forms by users, URLs generated by scripts, etc. You should always use the Unicode character encoding UTF-8 for your Web pages, and avoid ‘legacy’ encodings such as ASCII, Windows-1252 and ISO-8859-6 mentioned above. Do not use the UTF-16 Unicode encoding either.

It is important to note that it is not enough to simply declare your encoding at the top of the web page. You have to ensure that your editor saves the file in UTF-8 also. Most editors will do that these days, but you should check.

Read an Introduction to character sets and encodings here.

Use the <meta> tag with the charset attribute in your HTML page to indicate to the browser the character encoding you will be using in the page.

<meta charset="utf-8">

Alternatively, you can also use http-equiv and content attributes.

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

We recommend using the first one because it is much less complicated. You should also always use ‘utf-8’.

The meta declaration belongs inside the <head> element, and should be specified within the first 1024 bytes of your page. So the earlier it is mentioned in your code, the better.

W3C recommends placing it immediately after the opening <head> tag:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

...

</head>

</html>

Before we learn what HTML character references are, let’s look at how the need for them came about.

Try the following code in your HTML:

<p>Welcome to "HTML5 & CSS Fundamentals". The first tag we will be learning about is the <html> tag.</p>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Welcome to "HTML5 & CSS Fundamentals". The first tag we will be

learning about is the <html> tag.</p>

</body>

</html>

Did you notice the <html> tag is missing in your output? In this case, your browser mixed it up with an actual tag, although it was meant to be a part of the sentence as text. Because of this kind of confusion, HTML reserves certain characters. If you want to use these characters in your HTML, you need to use character references to display them.

All HTML character references can be written using either a name or number.

If you want to use a named character reference in your source code, use an ampersand symbol '&', followed by the name and a semi-colon. Names are case sensitive. For example, the following represents a no-break space:

There are two types of numeric character reference: ones that use decimal numbers and ones that use hexadecimal numbers. In each case, the number represents the code point number of the character in Unicode.

If you are using a decimal number, use an ampersand symbol ‘&’ , followed by the symbol ‘#’, then a decimal number and a semi-colon.

If you are using a hexadecimal number, use an ampersand symbol ‘&’ , followed by the symbols ‘#x’, then a hexadecimal number and a semi-colon.

The five special characters listed in the table below should always be written as character references if you want them to appear on your page when viewed by a reader:

| Symbol | Entity Name | Entity Number | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than ‘<’ | < | < | Div tag: <div> |

| Greater than ‘>’ | > | > | Div tag: <div> |

| Ampersand ‘&’ | & | & | Tom & Jerry |

| Non-breaking space - space that will not create a new line | |   | If you add multiple spaces, the browser will remove all but one. So you have to use this entity to add multiple spaces in your HTML page. |

| Quotes "" | " | " | Link to another section on the same page using the id of the element:

<a href="#timetable"> Displayed as: <a href=“#timetable”> " is generally encouraged for code. For an actual quotation, <q> or <blockquote> is preferred. |

We do not want these special characters to be processed by the browser as HTML code. Instead, you want it to be displayed to the user. So if you wish to display this in your browser:

<img src="images/test.png" alt="test image">

You have to write it like this in your HTML code:

<img src="images/test.png" alt="test image">

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>

<img src="images/test.png" alt="test image">

</p>

<p>

<img src=""images/test.png" alt="test image">

</p>

</body>

</html>

Some tolerant browsers will allow using the & character directly but not all. So you should use its character reference &. Check out these examples illustrating the importance of using the character entity & for &.

While it might be tempting to not use one of these character references when you notice that the browser produces the expected result anyway, it is a best practice to use character references for these five special characters using <, >, ", & and at all times. This is because you can never be sure what browser or application will be used to view your code, and how that will behave.

The " character reference is particularly useful for quotation marks within attribute values. Let’s say you want to add a title attribute to an abbreviation to provide an expansion of the abbreviation. If you try the code below in a browser and hover your mouse pointer on the text ‘HTML5’, it will show you the title text (it works like a tooltip). The title text in the source code includes quotes (around the number 5) like this:

<abbr title="Hypertext Markup Language "5"">HTML5</abbr>

The above will not display the number 5.

Replacing the quotes with its character entity will work:

<abbr title="Hypertext Markup Language "5"">HTML5</abbr>

Check out this jsfiddle link.

<p>Rest your mouse on the text below: (The number 5 is missing)</p> <abbr title="Hypertext Markup Language "5"">HTML5</abbr> <p>Rest your mouse on the text below: (5 is displayed when quotes is replaced with its character entity name)</p> <abbr title="Hypertext Markup Language "5"">HTML5</abbr>

It is also possible to use character references to represent other characters in your page. This is useful when you are unable to type the character itself, or when you can’t tell what the character is by looking at it (for example, a no-break space, or an invisible formatting character). There are predefined, named character references in HTML for several categories, these include:

For a list of named character references available in HTML, visit: https://dev.w3.org/html5/html-author/charref.

Any Unicode character can be represented using a numeric character reference. Apart from the characters used for HTML syntax (described in the previous unit), there is usually no need to use character references to represent characters.

All browsers are built using Unicode internally, which means that they are capable of handling all possible characters defined by Unicode. The best practice for symbols like copyright, currency symbols, math and arrows is to simply type them directly into the source code.

You can do this directly in the code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>This is © 2015. Breach will entail a fine of € 400</p>

</body>

</html>

There is no need for the © or € HTML character reference if you are able to type the character itself.

If you’d like to read more information about when to use character references and when not to use them, see Using character escapes in markup and CSS.

Children can be great at asking questions about things that most adults take for granted, and like to challenge assumptions.

While it’s a great sign of a curious and reasoning mind, it can be overwhelming, and you can’t really learn (or teach) everything at once. Some things are better to be taken on faith in the short term, until you fully understand the issue.

That brings up a term you’ll be hearing quite a bit in this class: “best practices”. It’s often said that bad programs can be written in any language, and we’ve found that to be true (at least in every language we’ve seen). Over time, developers learn that some habits are better than others, in other words that some habits, like avoiding redundancy and repetition, tend to make a program more clear and easier to understand and maintain than other habits, like using goto statements. It could also be about performance, i.e. in a given language doing a task one way may be faster than another.

A carpenter will tell you that if you want to hammer a nail, it’s best to do it in as few strikes as possible (e.g. 2 or 3). That may not be obvious to non-handy people like me, but I’ve been told that’s the best way by people with a lot more experience than I, so I’ll take it on faith (at least for now).

There are sometimes arguments about which are the best practices. New techniques are discovered, new ideas are born, and sometimes, fashions change. For our purposes and the duration of this course, when we use the term “best practice” you can trust that it is, even though we may not be able to explain it at that point in the course, so you’ll want to make it a habit.

The history of Web pages is such that browsers tend to be very forgiving of certain types of mistakes. If you miss a closing tag, it will often work the way you expect. It probably won’t crash, or ignore the document, or give up completely, but it might not appear quite the way you meant it to. Or maybe it does look like you want, but you do not want to depend on that. In general, best practices would call for one to do it properly, and not depend on the browser to patch it for you.

Because an HTML file essentially represents a tree structure, the open and close tags should always match, and there should not be any overlap with other elements. That is, you can have an element that is enclosed in another element, or you can have two elements side-by-side, but you can never have a situation in which part of an element is in another, but the other part is not.

<p>This is a <em>paragraph</em></p> <h1>Paragraph ahead</h1> <p>And here it is.</p>

The two examples above are fine because in each case either an element is wholly contained in another (<em> in <p>) or they are completely separate (<h1> and <p>). This, on the other hand, is not valid:

<h1>Part of this header is <p>in the</h2> paragraph below</p>

What happens in this case is what we call “undefined”. That just means that there is no telling how the browser will decide to handle it. It might decide to automatically close the <p> when it sees another close tag, or it could complain about an unexpected close tag at the header. Then it might complain again when there is a now unexpected close </p> tag.

If you played around with the minimal HTML file from the previous section, you might have noticed that you can get more minimal than that. For example, if you take out the “head” section completely, the browser will still render the page without complaint (at least Chrome will; Firefox does complain in the debugging console, but we will save that for week 4). In fact, you can even take out the “body” open and close tags (not the content, of course) and it will still work as expected. Not only that, if you take out the <!doctype> statement, it still works (and Chrome still doesn’t complain!).

What’s actually happening is that the browser knows roughly what to expect in an HTML page, so if it sees a file ending in ‘.html’ it will automatically stick some stuff in if it is not there already. It will typically make basic assumptions like: It is an HTML5 file, everything in there is content, so it goes in the <body> section, the <head> section is empty. If you right-click on an element and choose “Inspect”, you will see that the browser has included the <html> section containing the <head> and <body> sections, even though it wasn’t there in your file.

Note that we said “typically”. The current behavior of most browsers will handle this, but it is “undefined” so there is no guarantee that next module’s update won’t break it. To be correct and complete, you need the <!doctype> section and the <html>

section with <head> and <body>. In any case, it is a good idea (best practice).

Proper indentation is one way to make your code clearer and easier to understand:

<body> <h1>Here is a heading</h1> <p> <ol><li>List Item 1</li></ol> </p> </body>

The code above doesn’t give any sense of the structure of the document. By using indentation effectively, you can make it more clear, showing the nesting of elements:

<body>

<h1>Here is a heading</h1>

<p>

<ol>

<li>List Item 1</li>

</ol>

</p>

</body>

Consistent quoting of strings is also helpful, in part to avoid potential problems that can arise when you think something does not need quotes but it actually does.

Often, projects will have coding styles that everyone is expected to use so that everything looks consistent and developers can more easily read each other’s code. If you are creating the project, you can decide what the rules are (how many spaces to indent, single or double-quotes, etc.) but unless there is a good reason to change away from typical practices, it is usually best to adopt them.

Before we go any further, it’s good to understand a few technical details.

You might notice that code is not always consistent in how a given tag is written. We might say ‘<h1>’ in one spot and ‘<h1>’ in another. In this case, they are exactly the same kind of tag. Tag names are “case insensitive” meaning that it does not matter whether you use capital or lower case letters in writing them. In fact, you could write your body tag as ‘<body>’, but that’s not generally considered a good practice (Camel case/Snake case makes it harder to read). On the other hand, there are places where you want the computer to be “case sensitive”, meaning the computer will distinguish between upper-case and lower-case.

Obviously, you usually don’t want your text (that the user reads) to be case insensitive. You want your sentences and proper names to start with capital letters, but most other characters to be lower-case (unless you want to yell, in which case use “all caps”). You generally don’t want the browser to mess with that. You would probably be unhappy if the browser turned all your letters into lower case. And people might think you’re quite tightly wound if the browser converted everything to upper-case.

On the other hand, we usually do not want to worry about the amount of white space (spaces, tabs and returns) in between words and lines and paragraphs (well sometimes we do, but there’s a tag for that). In HTML, most extra white space will be ignored. By ‘extra’, I mean more than one space (or tab) consecutively. There are many places where you need to be sure to separate one thing from another with a space, but it generally doesn’t matter if you put more spaces in there, your result will look the same.

Thus, all three of the following elements should look exactly the same when you read them in the browser:

<H1> This is the Beginning </H1> <H1> This is the Beginning </H1> <h1>This is the Beginning</h1>

It might seem confusing at first, but this rule about white space is actually very convenient. The third option might be a bit too cramped for your taste, while the second might seem to take up too much room in your source code. Because it doesn’t matter to the browser how much white space there is, you can use white space to make your code more visibly organized and easier to read (note the use of indentation in the second <h1> element above).

Given that tag names are case insensitive (you can write them either way), you might think that everything in between < and > is case insensitive, but it is not that easy.

Attributes are case sensitive! We have not learned much about attributes yet, but when we do we will discover that they are case sensitive, thus these two elements will have different ’id’s:

<p id=ThisOne> <p id=thisone>

Even though they’re spelled the same, the differing cases indicate different names. Note that distinguishing different id’s solely by case (i.e. spelled the same but with different capitalization) is a really bad practice (opposite of best practice). Instead you can use capitalization in other ways, like CamelCase.

Finally, it will eventually be important to know about “strings”. Strings are just a series of characters. They could be any characters like “Dingbats” or “ABC123^&*@aeiou“. They can even contain spaces as in”This is a string.”. Because they are so wildly variable (they can essentially be anything you can type), the computer needs us to indicate where a string begins and ends, which is typically done with quotation marks, either single (’) or double (“). HTML tries to be helpful here.

You will find that in places where HTML is expecting certain types of strings (say a string without spaces), even if you do not use the quotation marks it will essentially insert them for you. Thus:

<p id=MyName> <p id="MyName"> <p id='MyName'> .... are all equivalent.

It is also important to know that, in HTML, double and single quotes are almost interchangeable, but they have to match. If you start a string with a double quote, the computer will not end it until it sees another double quote. Any single quotes will be happily considered part of the string, which is handy if you need quotation marks in your string. Because of this, if you create a string as ’“quote” ’ (single quotes containing a double quoted string), your string will have the letters <space>-“-q-u-o-t-e-”-<space> (with double quotes in the string and spaces outside those) as opposed to “quote” which will just have the letters q-u-o-t-e (no quotation marks or spaces in the string). Nevertheless, best practice is to be consistent in your quotes, so it’s best to quote them all the same way, even if the browser would understand it anyway.

The idea is to take advantage of these flexibilities to create clean organized code that is easy for a human to comprehend. I guess you could sum it all up with these simple dictum:

Are they consistent with each other? Are there some rules that don’t seem to make sense?

Can you find other style guides or coding standards that agree or disagree with some of the suggestions in one of these guides?

Now you can create a simple, empty, HTML page, and you know what tags are, though we have not said a lot about specific tags, what they mean, how many there are, etc. We will start with the ones we have already seen:

<!DOCTYPE <span class="dt">html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>A TALE OF TWO CITIES</h1>

<h2>A STORY OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION</h2>

<h2>Book the First—Recalled to Life</h2>

<h3>I. The Period</h3>

</body>

</html>

Though you theoretically should not think about what it looks like, it will typically appear as large, possibly bold text in your document, to mark a separation or beginning of some new section. <h2> is usually a bit smaller, and <h3> smaller yet and so on down to <h6>. This allows logical nesting of sections, though they should not be nested too deeply. Try not to skip levels of headers when nesting them. Headings are really useful for some assistive technology users and missing levels can be confusing.

<!DOCTYPE <span class="dt">html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>

This is a paragraph.

It may or may not be indented but there should be a line

break at the end. Typically the last line will not stretch

as far to the right as the rest of the lines. Often there

is extra space between one paragraph and the next.

</p>

</body>

</html>

You might notice that when discussing how these different elements are

rendered (i.e. what they look like to the end user), you will find

words like “typically”, “possibly”, and “generally”.

It is a little picky. As you will learn in Module 3, it is possible to change the

styling of one element to look like just about any other element.

You could style a <p> element so that it looks like an <h1>,

though best practice would be not to do that.

There are a lot more tags, but we will just cover a few more for now, mostly because they are straightforward to use and you can see the effect in your Web page when you use them:

Brevity is beautifulwould be rendered as Brevity is beautiful.

Early to bed and early to rise, makes someone healthy, wealthy and wise - Benjamin Franklin

Thus a list in HTML would look like this:

<ul> <li> First item in list </li> <li> Second item in list </li> . . . </ul>

There are a couple more tags we want to bring up at this point, but first a disclaimer. We have been emphasizing the general rule that HTML is for the logical structure of your content, not what it looks like. Well, this is not entirely true. There are some HTML elements that are primarily used to invoke certain formatting.

That which we call a rose <br> By any other name would smell as sweet That which we call a rose <br> By any other name would smell as sweet